The road to Spinosaurus III: Of chimeras and leg proportions

/Do all of the front bits of FSAC-KK 11888 go with the aft parts? Does the new tail change that question?

In order to produce an updated skeletal reconstruction of Spinosaurus you have to be able to settle on its proportions. I have previously mentioned that FSAC-KK 11888 is the proverbial elephant in the room when it comes to this challenge, and the reduced hind legs of the FSAC specimen are the proverbial….bigger elephant? Woolly mammoth in the room? What I’m saying is someone is going to be unhappy with my conclusions no matter what I find, so I’m going to walk through my reasoning on the subject here in some detail. Apologies in advance, but this will be the longest entry in this series, by a significant margin.

Background

When Nazir Ibrahim and coauthors published a new specimen of Spinosaurus in Science back in 2014, it promised to revolutionize everything we know about the enigmatic theropod. The authors claimed that by integrating FSAC-KK 11888 with previously known Spinosaurus material (i.e. the destroyed Stromer material plus referred, isolated bones found across northern Africa) a truly astonishing new portrait of the species emerged. In addition to the new “M-shaped” sail I discussed last time, the new-look Spinosaurus was portrayed as as knuckle-walking, quadrupedal theropod with a surprisingly reduced pelvis and hind legs. These were presumed to be adaptations for the specialized aquatic-pursuit predator role the authors advocated, in which they viewed Spinosaurus as a dinosaurian analog to early whales.

As most of you already know, the new-look Spinosaurus generated its share of controversy. While most paleontologists had previously accepted that Spinosaurus ate fish and lived in and around water, the rest of the claims have been questioned repeatedly. Papers by Don Henderson and Dave Hone & Tom Holtz challenged the swimming ability and adaptations for aquatic pursuit predation*, while Evers, et al (2015) questioned whether the FSAC specimen was really a single individual, and whether there was more than a single species of spinosaur in northern Africa at the time. Skeptical takes were discussed in detail by Mark Witton and Jaime Headden. I wrote a couple of blog posts myself questioning the new-look proportions.

Others were more supportive. Andrea Cau has written in defense of the proportions and single-individual status of the FSAC specimen several times on his excellent Theropoda blog. Duane Nash also wrote a series of posts about Spinosaurus as hippo-like aquatic punters. In an excellent example of constructive dialog, the authors from the 2014 paper reached out to Mark Witton and myself to clarify their viewpoints (more on this below). And earlier this year a series of papers were published examining the stratigraphy, taxonomic questions, and the newly described tail, and all made the case that FSAC-KK 11888 is a single individual with oddly-proportioned anatomy.

Of Chimeras and FSAC-KK 1188

Many people have opined via social media, etc., about whether they find the hind limb proportions proposed by Ibrahim, et al. “likely.” But in science we need to try our best to not let our preconceived notions drive interpretations. The question isn’t whether any given set of proportions are “reasonable”, but rather how good is the data supporting them. So how good is the data here? As near as I can figure, there are basically 3 ways FSAC-KK 11888 may be misinforming us about the proportions of Spinosaurus:

1) The measurements reported for the specimen are in error.

2) FSAC-KK 11888 is not a single individual

3) FSAC-KK 11888 is not Spinosaurus (regardless of whether it is one individual)

It’s technically possible to question the measurements themselves, but without directly accessing the specimen (or casts) I don’t view this as a productive line of inquiry. While everyone is susceptible to making errors, there’s little reason to assume the authors can’t competently wield a measuring stick and/or record the results. It’s also worth noting that photographs can lie, so apparent discrepancies between photos and published measurements can’t be usefully resolved without access to specimens. On the other hand, seeing as this entry is plenty long enough as-is, I won’t be taking you on a deep dive into the taxonomic dispute over whether there is more than one species of spinosaur in the Kem Kem beds, and whether it (or they) are likely to the same species as Stromer’s material. Even those who largely endorse the findings of Ibrahim, et al. have differing views on the question of taxonomy, but if we stipulate that the FSAC remains at the least come from a close relative of Spinosaurus, and I think we can, the taxonomic debate may not matter much to the proportions anyways (although it could mean something about referring isolated material).

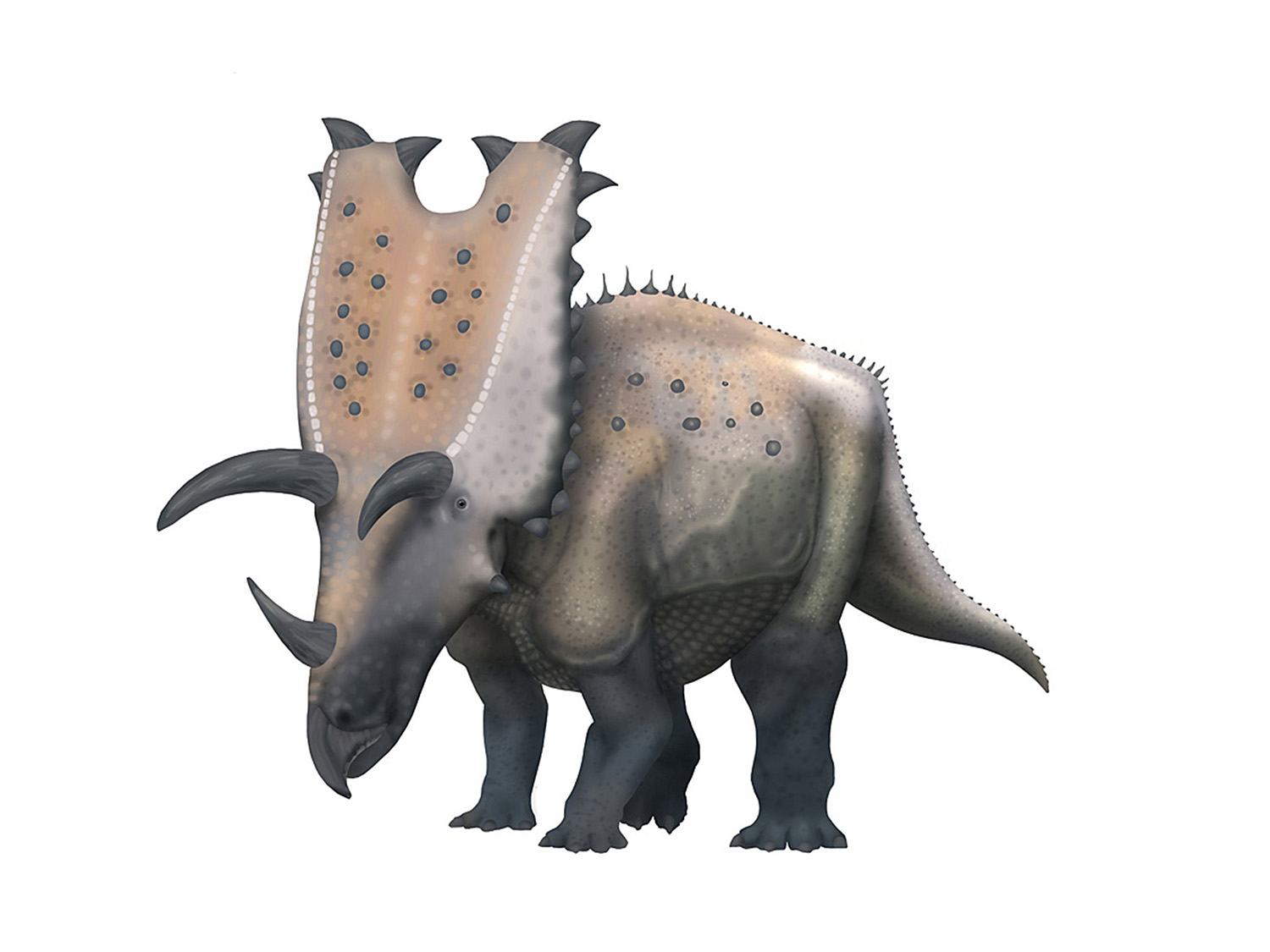

Schematic skeletal of FSAC-KK 11888 with the new tail from 2020 and some updated preservational information. Aside from the tail this is still using the proportions from Ibrahim, et al. (2014).

But there may yet be reason to question whether FSAC-KK 11888 is a single individual. Some will be exasperated by this claim, especially in light of the recent spate of papers by team-Ibrahim that claim to lay this to rest. After all, the recently described tail came from the same quarry, and it perfectly matched previously collected caudals. The new toe bone matches the previously collected ones. There are new skull fragments! Some new chunks of neural spine collected in the float! Why would you bring this up again Scott?!!

To be sure, the recent papers have probably put to rest the idea that the FSAC specimen is a random hodge-podge of multiple individuals. But these additional finds fail to address what to my mind is the key question: Whether the hind legs go with the dorsal centra. The 2020 papers mentioned above have made an overwhelming case that the pelvis, hind legs and tail all go together, so perhaps the question is better restated as whether the rear half of the animal goes with all of the material in the front half (and if not, which parts)?

That link between the rear half and the dorsal vertebrae is more circumstantial. As covered in the original 2014 Science supplementary online data, the Evers 2015 Sigilmassasaurus paper, and further detailed by Andrea Cau, the earliest bones referred to FSAC were collected by a local commercial fossil dealer, who sold this material to two different museums in 2008-2009. It was only after those museum groups realized they had purchased spinosaur fossils from the same person that they returned to him and were shown a site with more material in it. At that point additional spinosaur material was excavated in a controlled setting starting in 2013, and continued at least up through the new tail published this year. Alas, the 3 dorsal centra and majority of the presacral material seems to have originated during the “material collected by a local collector and sold to two-different museums” part of this story.

This is not meant to invoke a commercial vs academic collecting debate. It is both indisputable that there are well documented cases of local collectors assembling composite specimens and/or telling paleontologists purchasing fossils what they want to hear, while also indisputable that this doesn’t mean it happened in this particular case. But given that the unique proportions of FSAC-KK 11888 depend entirely on the association of (seemingly) oversized torso material, having the dorsals collected under these circumstances is unfortunate. The recent addition of the new tail and hindlimb material that matches existing FSAC tail and hindlimb material does little to solve this problem, as there’s no reason to doubt the association of the tail and pelvis with the hind legs. In fact, it is worth noting that the hind limbs don’t actually look all that reduced in size when compared to the pelvis or the caudals. But the hind legs, pelvis and caudals all look reduced compared to the dorsal centra of FSAC-KK 11888. The FSAC caudals average less than half the length of the dorsals, unlike the condition in relatives like Baryonyx, Suchomimus or Ichthyovenator where they approach or even exceed the length of the dorsals.

Of course it’s possible that Spinosaurus had different pelvic, hind limb, and tail proportions than it’s relatives. And to be clear, a chunk of possible splenial (lower jaw bone) and some chunks of neural spine sections were found in the most recent excavation (although the spine chunks, at least, were recovered from float rather than in the quarry). But that doesn’t tell us whether the bulk of the presacral material collected under uncontrolled circumstances (especially the dorsal centra) were in fact collected from the same quarry and/or come from the same individual. For definitive evidence we would either need additional dorsal vertebrae to emerge from the FSAC quarry, or for another specimen to be collected under controlled circumstances to confirm or refute the connection between the large dorsal centra and the reduced pelvis/hind limbs/tail in Spinosaurus.

Leg proportions

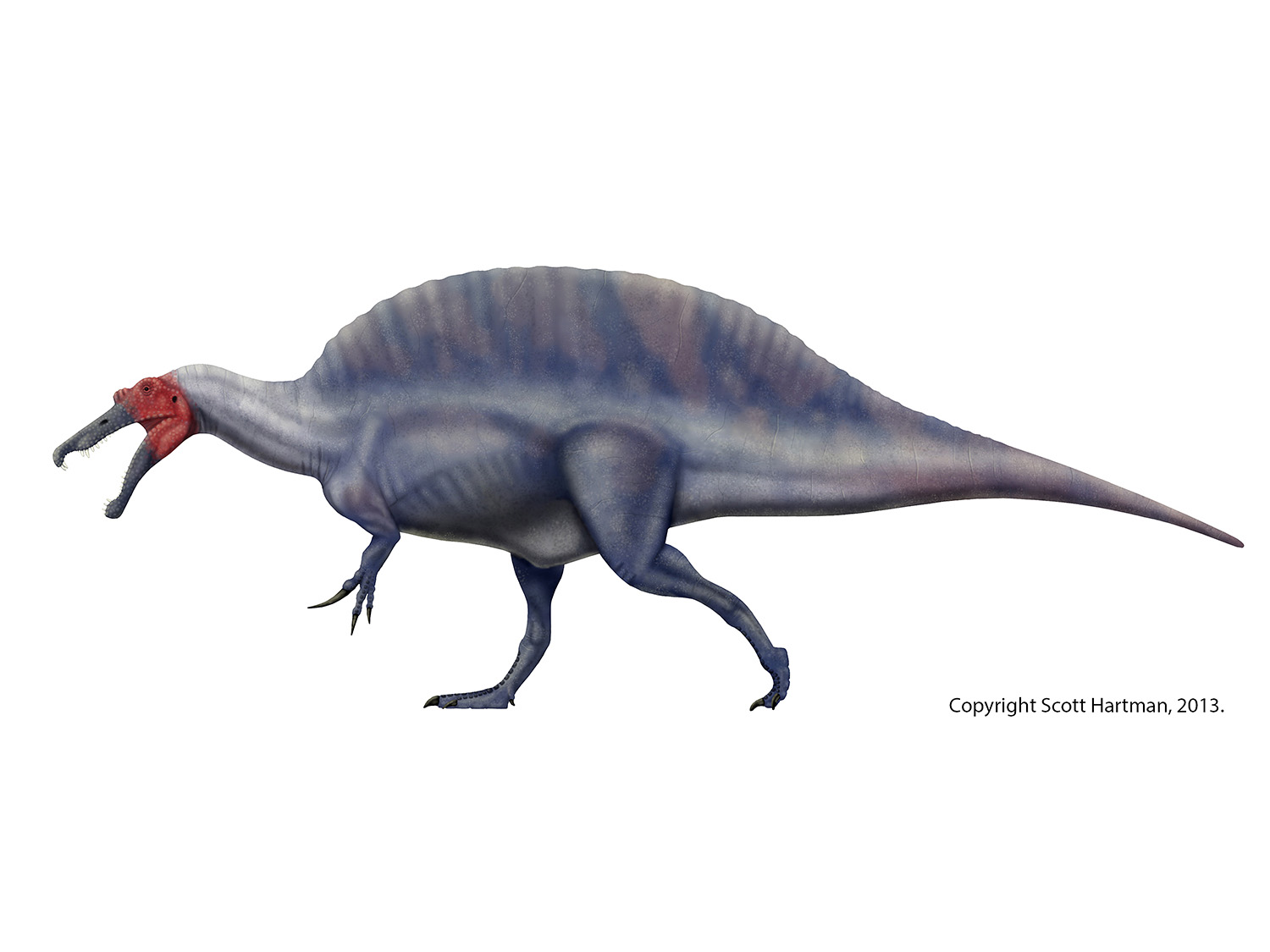

The remains of Spinosaurus B, as figured by Stromer in 1934.

Another argument has been put forward: What if we could compare the leg proportions of FSAC-KK 11888 to a prior specimen of Spinosaurus? If those matched it would be unlikely to be a coincidence, would it not? This very point has been argued by Andrea Cau, who compared the length of a dorsal centra to the tibia as a proxy for torso to leg proportions in both the FSAC specimen and Stromer’s Spinosaurus remains. Of course Stromer’s Spinosaurus material was destroyed, and the type specimen doesn’t have any limb material. Here is where a second, less complete specimen described by Stromer becomes suddenly important. Designated “Spinosaurus B” by Stromer, both a tibia and some dorsal vertebrae were among the material referred to this second specimen. And while it too was destroyed during the second world war, we have Stromer’s figures, description and measurement tables available in his 1934 paper on the dinosaurs of the Bahariya Formation.

Stromer (1934) is written in German, but an English translation** by Sven Sachs is available on the excellent Polyglot Paleontologist website (along with many other treasures). Stromer himself might argue that Spinosaurus B is not a home run to use as a point of comparison here - Stromer doubted the remains were from a single individual, writing “…some of the associate remains can, because of their sizes, not belong to one individual”, and clarifies further that “It remains questionable if the small femur and tibia as well as two phalanges…even belong to Spinosaurus” (Page 21 of Stromer 1934, 22 of the Sachs translation). Yet if Spinosaurus did have unusually reduced hind limbs it makes sense that Stromer would make this mistake, since he lacked any other context to interpret them in. So the real question for us is, do the limb proportions of Spinosaurus B and FSAC-KK 11888 match?

In his blog, Andrea Cau reported that the dorsal centra to tibia ratio is 25% in FSAC and 23% in Spinosaurus B (higher values mean shorter legs). Evers, et al. (2015, page 72) reported a larger difference of 26.9% in FSAC to 23.3% in Spinosaurus B. I’m fairly certain this discrepancy can be attributed to which FSAC dorsal they used - Evers reported using the centrum identified as the 8th dorsal (which is reported to be 180 mm long), while the other two mid-dorsal centra are reported as 170 mm long, which works out to 25.4% (presumably Cau rounded down for simplicity). Problem solved? Well…the difference between the two calculations is, but not the interpretation. As Evers notes, a 4% difference between the dorsal to tibia ratio is as large as the difference between Allosaurus and Elaphrosaurus, two theropods one would be unlikely to mistake for having the same limb proportions. There’s also the question as to which is the “right” dorsal vertebrae to choose for this comparison? To avoid this problem I prefer to average the lengths of the known mid-dorsals in each specimen before calculating the dorsal to tibia ratio. This also side-steps questions about whether the vertebrae in both specimens are referred to exactly the correct position in the spinal column. But I think there may be a bigger problem here: I’m fairly certain both are comparing apples to oranges (for non-native English speakers, I mean they are not comparing the same thing).

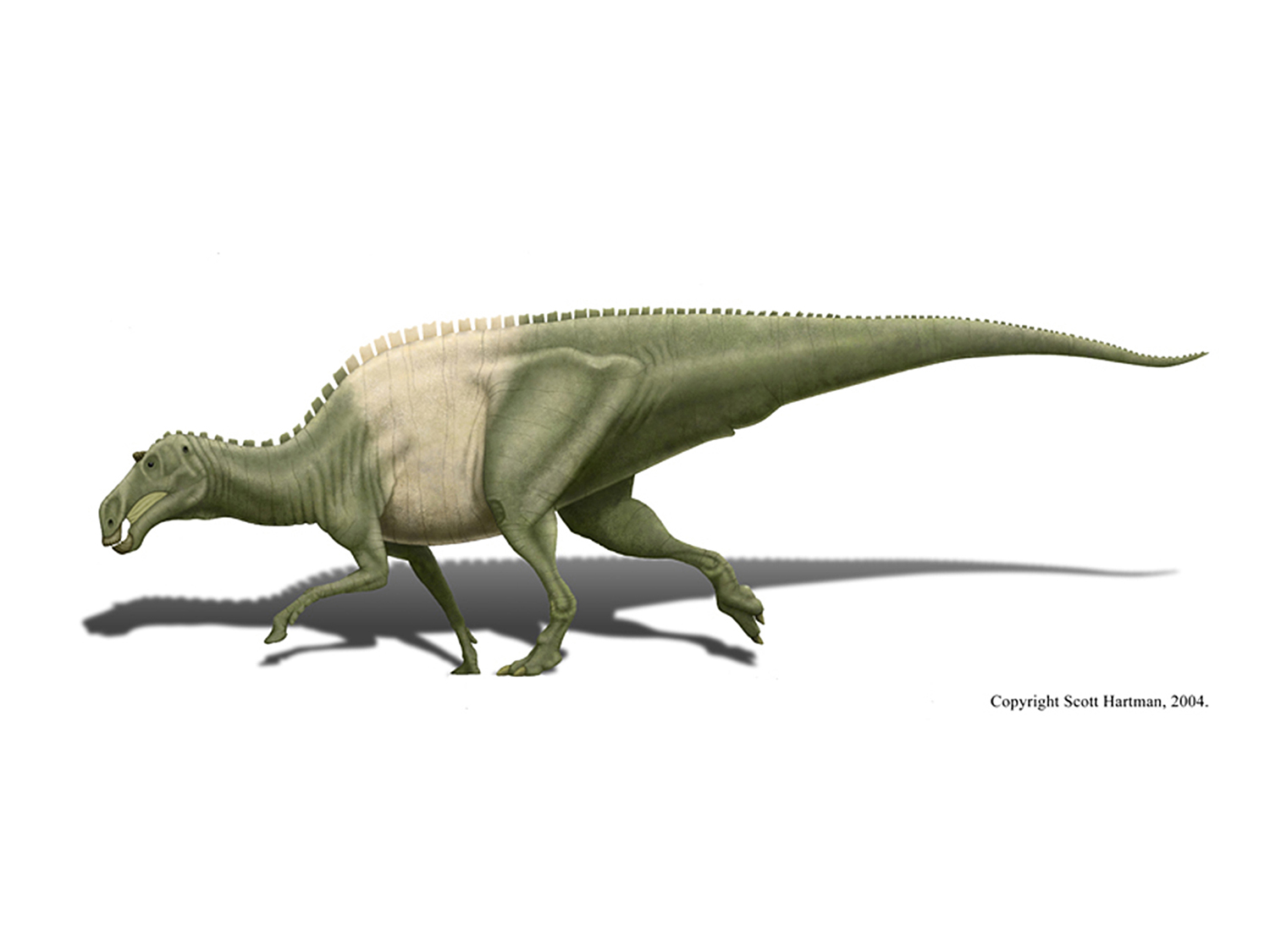

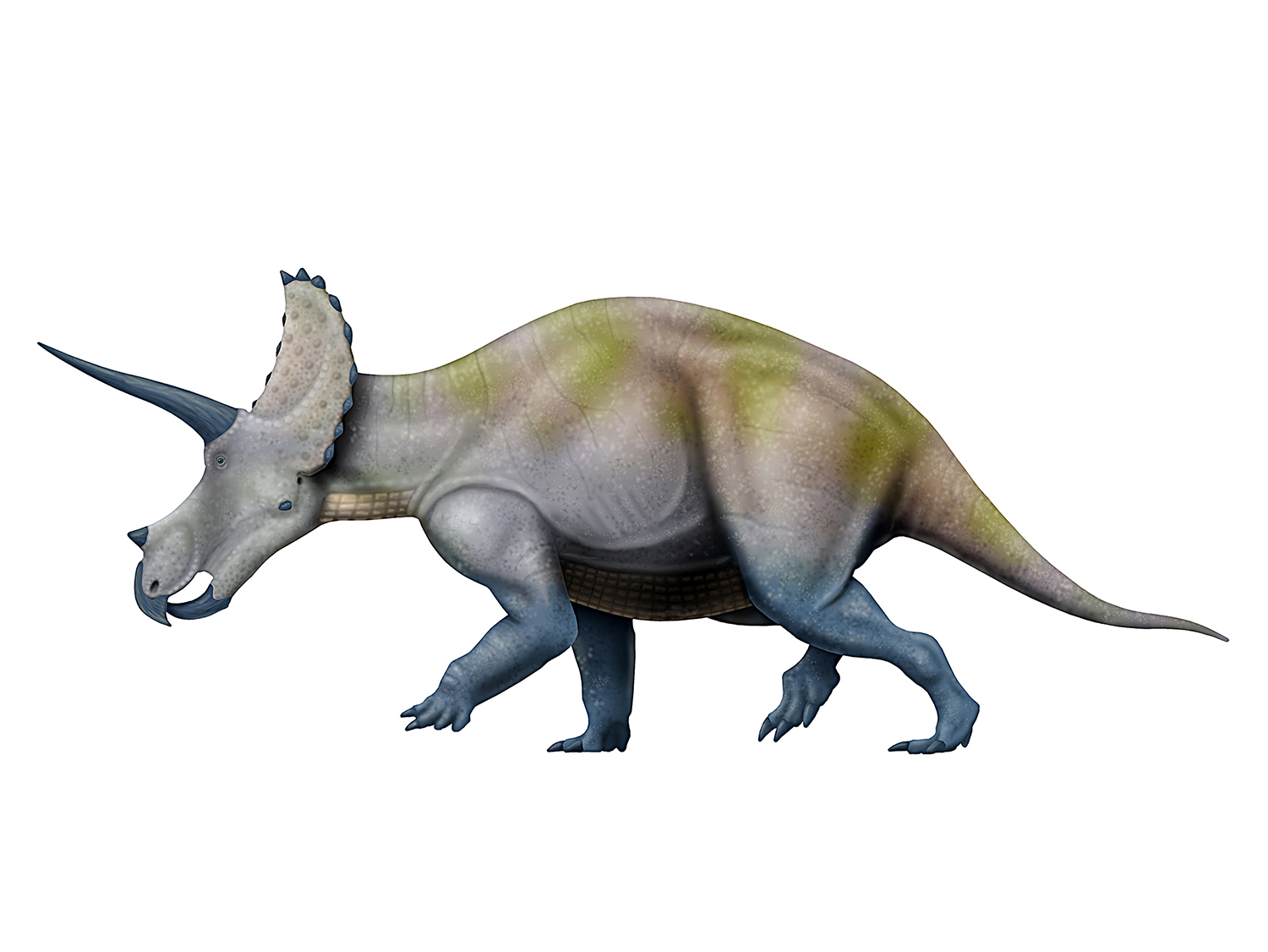

Different ways to measure the length of a vertebrae: Either the longest length of the centrum, or the shorter rim to rim (RTR) length. Image modified from Ibrahim, et al. (2014) supplemental figure S2.

Relevant sidenote: Some of you may recall in one of my original posts in 2014 on the FSAC Spinosaurus I questioned whether the FSAC skeletal reconstruction put forth by the authors matched the measurements they published in their supporting online supplementary data. In that post I used the length of a dorsal vertebra to check the rest of the skeleton, and it appeared as though the hind legs, tail, and pelvis were much too small. Mark Witton replicated my measurements and found the same thing. Despite near-identical results we were both unwittingly in error, because the authors of the 2014 paper reached out to us to clarify that their vertebral measurements table was not reporting the entire length of the vertebral centrum as we had assumed, but were instead reporting “rim to rim” measurements that did not include the condyle (the anterior ball) in the length. As you can see in the adjacent image, this makes a huge difference (the full centrum length in this case is 33% longer than the rim to rim measurement). And sure enough, when Mark and I checked the scaling based on rim to rim measurements the 2014 model checked out.

This is exactly where I believe both Cau and Evers, et al. ran into a problem with their comparison, because Stromer’s tables explicitly label his centra measurements as “größte Länge”, or greatest length. Greatest length clearly indicates Stromer is reporting the entire length of the centrum, not a rim to rim measurement. Since the presacral vertebrae of Spinosaurus are strongly opisthocoelous (they have a ball on the front) this means the “greatest length” dorsal to tibia ratio of Spinosaurus B is a very different thing than the “rim to rim” dorsal length to tibia ratio of FSAC-KK 11888.

Unfortunately the Spinosaurus B remains are no longer with us, and I’m not comfortable using the drawings in the 1934 “1/3 natural size” plates to try and figure out a rim to rim estimate. Worse, not all the dorsal vertebrae of FSAC-KK 11888 have been figured sufficiently for precise greatest length measurements to be estimated either. I could just add the extra 33% length to the FSAC rim to rim measurements, as seen in dorsal 4 (or 5 , shown in the vertebral figure above); that certainly results in a massive difference between the dorsal to tibia ratios of FSAC and Spinosaurus B, but it also undercuts what I said earlier about trying to average the available dorsals for each specimen so as not to cherry-pick data***.

This means I am dealing with imperfect data, but analyzing publicly available photos of the FSAC vertebrae I came up with a more conservative “correction” ratio of 26.3% that needs to be added to the FSAC the dorsal vertebrae to make it that same type of measurement as Stromer was reporting. If you are understandably concerned about the use of photos this way, feel free to use the less conservative D4 (or 5) estimate of 33%.

My results? I get a dorsal to tibia ratio of 23.96% for Spinosaurus B, very similar to what was found by both Cau and Evers, et al. But I get a ginormous 32.76% for FSAC-KK 11888, making the FSAC tibia far shorter relative to its dorsals than in Spinosaurus B. That would mean they are not even remotely close to the same proportions once you compare measurements using the same vertebral landmarks, far outside of the variation we see within a species today. While I will need to someday recheck these numbers when better data becomes available, I do not anticipate it will close the yawning chasm between the limb proportions of the two specimens.

Conclusions?

As near as I can tell, the proposed leg proportions of FSAC-KK 11888 simply do not come close to matching those Stromer recorded for Spinosaurus B, and it seems prior attempts that found more congruent results were not comparing the same vertebral landmarks between the specimens. Does that mean the FSAC specimen is a chimera, at least as regards some of the presacral material that was privately collected under uncontrolled circumstances? It certainly raises suspicions, but in the end I can’t say for certain; I hope more material comes to light from the FSAC quarry to clarify things. But if the FSAC proportions are valid they do not match Spinosaurus B, and it would call into serious question whether FSAC-KK 11888 really is Spinosaurus.

For my purposes here, despite Stromer’s concerns about whether the associated Spinosaurus B material came from one individual I went with Spino B proportions to guide my skeletal reconstruction. The similarity in gross morphology (but not proportions) between FSAC and Stromer’s material strengthen the idea that all of Spinosaurus B is spinosaurid, and presumably therefore all Spinosaurus. This strengthens the case that Spino B is a single individual (though it’s not an open and shut case, to be sure). On the other hand, if both Spino B and FSAC are resolved as single individuals, the FSAC proportions are far too different from Spinosaurus B to be considered the same thing, so FSAC would probably not be Spinosaurus. And though FSAC would still be a spinosaurid, it’s Spinosaurus I am attempting to restore here. I do think it’s reasonable to use the FSAC material to fill in missing parts in a Spinosaurus skeletal, just being sure to rescale them to match the proportions of Spinosaurus B.

I think this is the main CYA portion of these articles, so I’ll post my revised Spinosaurus skeletal in the next one. I probably have another post on Spinosaurus ecology coming, and one with a couple new and revised skeletals of some other spinosaurs, and then I hope to never, ever look at a spinosaur paper ever again.

You know, until the next one…

This post was brought to you by Permia

Not only do the good folks at Permia like Spinosaurus, they think it’s cool enough they might want to use it on their always-excellent merchandise. You should go check it out!

Work cited

Evers, S. W., Rauhut, O. W., Milner, A. C., McFeeters, B., & Allain, R. (2015). A reappraisal of the morphology and systematic position of the theropod dinosaur Sigilmassasaurus from the “middle” Cretaceous of Morocco. PeerJ, 3, e1323.

Henderson, D. M. (2018). A buoyancy, balance and stability challenge to the hypothesis of a semi-aquatic Spinosaurus Stromer, 1915 (Dinosauria: Theropoda). PeerJ, 6, e5409.

Hone, D. W. E., & Holtz Jr, T. R. (2017). A century of spinosaurs‐a review and revision of the Spinosauridae with comments on their ecology. Acta Geologica Sinica‐English Edition, 91(3), 1120-1132.

Ibrahim, N., Maganuco, S., Dal Sasso, C., Fabbri, M., Auditore, M., Bindellini, G., ... & Wiemann, J. (2020). Tail-propelled aquatic locomotion in a theropod dinosaur. Nature, 581(7806), 67-70.

Ibrahim, N., Sereno, P.C., Varricchio, D.J., Martill, D.M., Dutheil, D.B., Unwin, D.M., Baidder, L., Larsson, H.C., Zouhri, S. and Kaoukaya, A., (2020). Geology and paleontology of the Upper Cretaceous Kem Kem Group of eastern Morocco. ZooKeys, 928, p.1.

Ibrahim, N., Sereno, P. C., Dal Sasso, C., Maganuco, S., Fabbri, M., Martill, D. M., ... & Iurino, D. A. (2014). Semiaquatic adaptations in a giant predatory dinosaur. Science, 345(6204), 1613-1616.

Smyth, R. S., Ibrahim, N., & Martill, D. M. (2020). Sigilmassasaurus is Spinosaurus: a reappraisal of African spinosaurines. Cretaceous Research, 104520.

Stromer, E. (1934). Ergebnisse der Forschungsreisen Prof. E. Stromers in den Wüsten Ägyptens. II. Wirbeltier-Reste der Baharije-Stufe (unterstes Cenoman). 13. Dinosauria. Abhandlungen der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Abteilung, Neue Folge (in German). 22: 1–79.

* As an interesting footnote to all this: Ibrahim, et al. (2014) coauthor Paul Sereno gave a talk at SVP in 2015 testing Spinosaurus swimming simulations (coauthored by Frank Fish and Nathan Myhrvold). In person it was much less impressed with the swimming ability of Spinosaurus than either the 2014 paper or the presentation abstract implied.

** In a few cases I double-checked key translations with both Google Translate and a German to English dictionary, but ultimately the fumblings of myself and AI translation did little other than confirm the quality of Mr. Sach’s translation.

*** There are other solid reasons to want to average vertebral lengths, as dinosaurs seem to show higher variability in vertebral length from one to the next, something I examined in depth for my dissertation. More on that…someday!