Taking a 21st century look at Dimetrodon

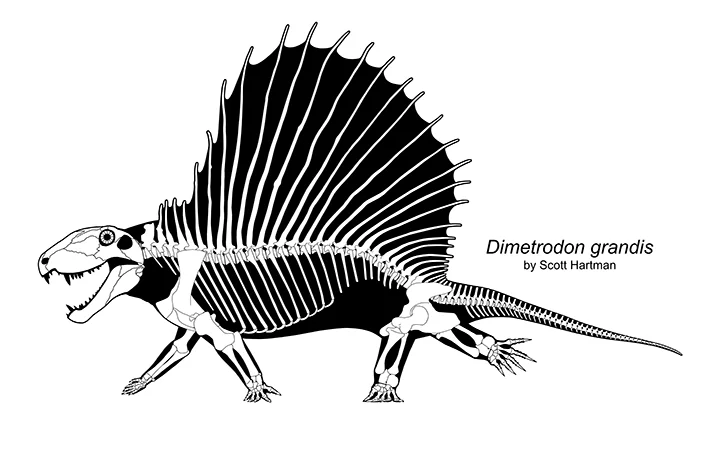

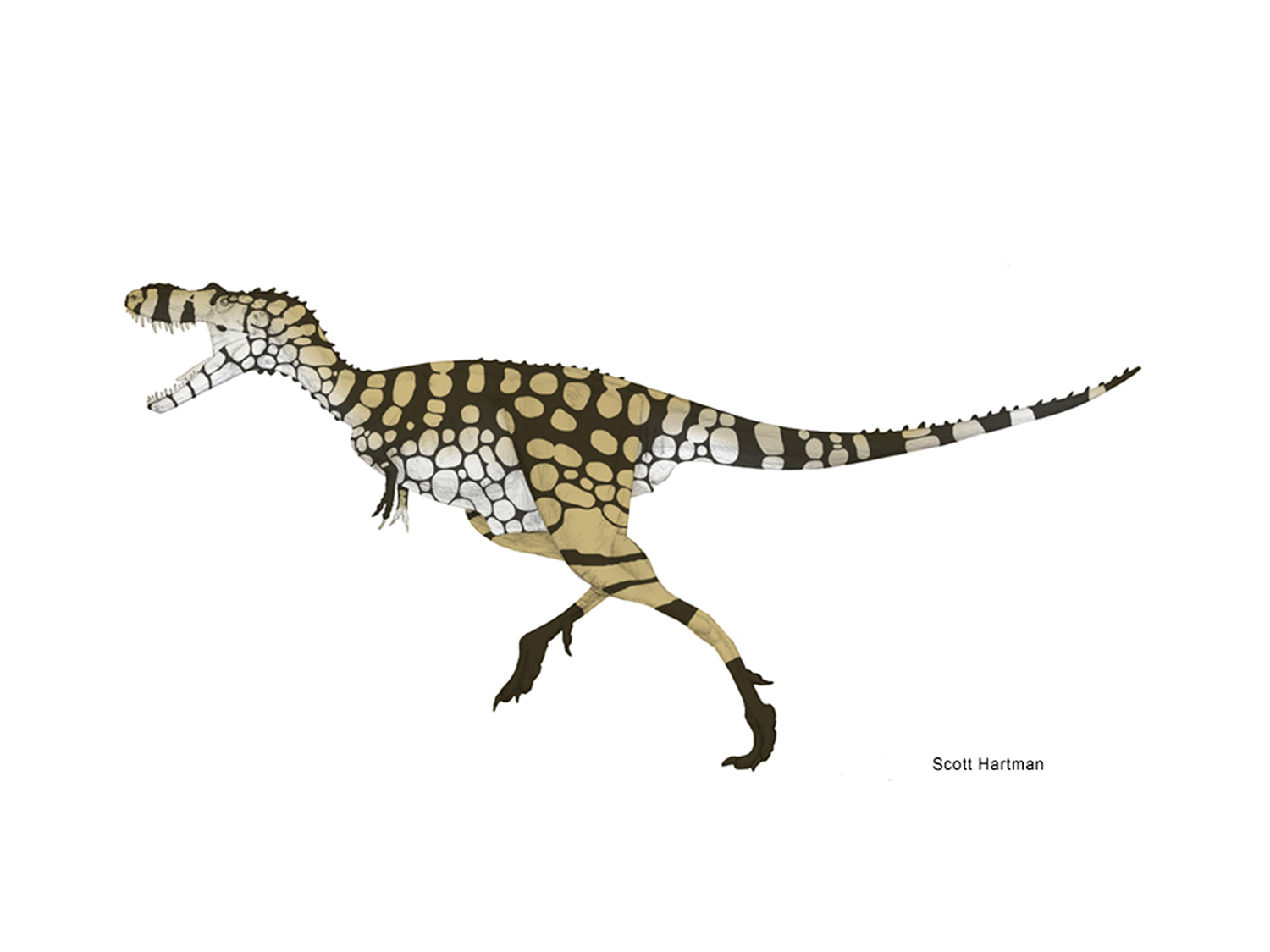

/Today I have something I’m excited to share with you: my skeletal reconstruction of Dimetrodon grandis. It looks quite a bit different from existing skeletal reconstructions, so I’m also going to take a more in-depth look at the underlying data. But first, let’s take a look:

Why Dimetrodon? Aside from the fact that it’s awesome?! OK, I admit that without external impetus I would probably not have gotten around to working on any pelycosaur skeletal reconstructions for a fair bit yet. But for the last year I’ve been working with Permia to help them design paleo-themed clothes and merchandise, and one of their early requests was for a skeletal reconstruction of the iconic sail-backed stem-mammal.

So how does the new skeletal differ from past reconstructions? There are quite a few ways, but for now I’ll highlight three of them: The sail with semi-emerging spines, the curvature of the back, and the high-walk pose. Let’s unpack each one:

Sail shape: If you look at recent Dimetrodon paleoart you will see there has been a big increase in the variety of ways in which the sail is being restored. Some have the spines almost entirely protruding while others have the sail covering the entire thing, and almost everything in between. Much of this interest has stemmed from research done by Rega, et al., (2012) that looked at the pathologies found in the tall back spines of Dimetrodon.

The authors observed that some of the neural spines had broken and later healed. This is strongly suggests that at least part of the spine was embedded in a sail (or similar tissue) that kept them in place after breaking so they could heal. But they also observed that the tops of the spines were often bent, sometimes severely, which suggested that the top of the spines were not embedded in a sail. Further confirmation of this “emerging from the sail” configuration comes from the surface texture of the neural spines. The spines shift from a roughened texture where they are embedded in back muscles, to a texture consistent with being in a sail (e.g. impregnated with Sharpey’s fibers), to a smooth texture at the top, where they most likely became spines that stuck out of the sail.

So it appears that Dimetrodon had a serrated, multi-spined sail in life, though exactly how much of the neural spines stuck out isn’t entirely clear - the specimen discussed above came from a different species of Dimetrodon, D. giganhomogenes, and the condition may have varied between species, or possibly even within a species between genders and/or during ontogeny.

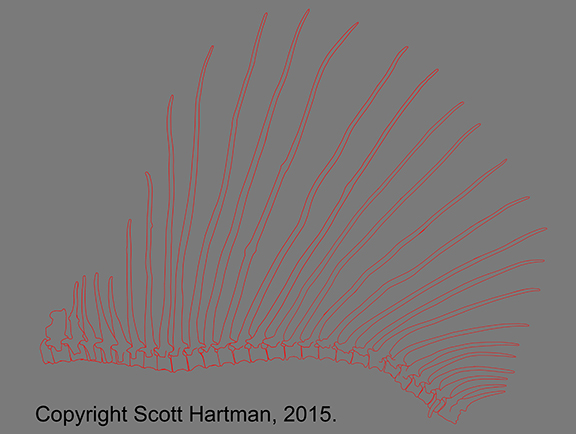

A work in progress snapshot of the dimetrodon neck and

Back curvature: If you want to know what an extinct organism looked like in life, the shape of the vertebral column is one of the most important things to get correct. Based on the many existing skeletals I had assumed that there was no controversy to be found here, as they all showed a generic series of gently arched back vertebrae with a straight neck and tail. But as I worked to restore the backbone of D. grandis I was immediately vexed, as many of the vertebral bodies (the centra) were quite strongly bevelled, which generally indicates curvature in the spine. Moreover, they weren’t curved randomly, they instead curved down in the neck and the posterior part of the back, and up at the transition from the back to the neck - in other words, they were curved in the same manner as seen in more advanced therapsids (and in many mammals). I spent a really long time on the neck and back - coming from a background based on archosaurs, and with every skeletal of Dimetrodon ever done seeming to show something else I triple-checked everything.

A couple of things have made me comfortable with this solution - first was that the neural spines themselves support it. If I forced the backbone to look like other skeletals the neural spines ended up clumping together in the areas that should be curved down. If I let them articulate the way the bones suggest then the spines maintain a reasonable, even spacing down the body. Another thing that helped convince me looking at other specimens; my skeletal is predominantly based on the Smithsonian specimen of D. grandis, but looking at other specimens I saw evidence of these same curves in several other specimens - for example in the AMNH D. incisivus specimen the same curve in the back just ahead of the hips is quite obvious (in some mounts you can see gaps between the vertebrae that were created when the back was straightened out).

The odds seem small that this bevelling of the vertebrae could be diagenetic (that is, deformation caused after burial) since the neural spines would have to also be bent to compensate. The fact that is appears in many other specimens also makes it more likely that this is a real phenomena, and not an artifact from a single specimen. As a final bit of positive reinforcement, I chatted with several Permian synapsid researchers at SVP in October and received only positive feedback. Phew!

The high walk pose: OK, I admit it, it’s a “high run” pose. By “high walk” I was referring to the semi-sprawled gait we see at times in extant crocodilians. Traditionally Dimetrodon has been portrayed using a lizard-like sprawl, but in the last couple of decades researchers have discovered trackways given the name Dimetropus. These trackways, which appear to have been made by Dimetrodon or a synapsid closely related to Dimetrodon, show an animal moving with a more upright posture, holding its belly and tail well clear of the ground.

It seems clear that Dimetrodon could sprawl when it wanted to (perhaps while at rest, or simply when it wanted to stay close to the ground), but the trackways also attest to frequent use of a more upright (semi-sprawling) posture. And if Dimetrodon was in a hurry, the more upright pose seems like the clear stance to adopt. Keen observers will note that I have actually spent a lot of time reposing my theropod skeletals to make them not be running. I’m not having a change of heart - like other skeletal poses I created for Permia this is a one-off pose for them. It’s a reasonable-yet-dynamic pose that hopefully helps make for desirable clothing and other other items, but it is specifically for their merchandise. As soon as time allows I’ll release a more general pose that will be sauntering at a more sedate pace (that is the one I will upload to my galleries).

False consensus & other thoughts: When I began this skeletal reconstruction I thought this would be an easy project, since Dimetrodon skeletals up until now have looked more or less the same. Now that I’ve spent a serious chunk of time working on them, it turns out that this similarity wasn’t due to informed consensus, but rather that everyone appears to have more or less recycling Romer’s 1927 skeletal, right down to the limb pose! I don’t want to name names, but you can see Romer’s skeletal below, and if you Google “dimetrodon skeletal” you can see for yourself just how pervasive the habit of “taking direct inspiration” from Romer’s skeletal has been.

I expect people will want to know if this should be the new base-look for all Dimetrodon species, but unfortunately it’s hard to say at this point. Dimetrodon is a genus with a dozen or so valid species (depending on who you ask) spread over 20+ million years. Those species range in length from under a meter to giants more than five meters long! In short, Dimetrodon species could have had a lot of diversity in their backs, sails, etc., and it will take more more to find out. But I do feel comfortable saying that at the least Dimetrodon grandis looked quite different from the Romer-cloned version we’ve been using for most of the last century.

Thanks to Permia: I also want to take a moment to thank the team at Permia, as I quite simply would not have tackled this skeletal without their initiative. Their vision for a company that embraces both science and style is more than just glib marketing talk; they’ve been extremely supportive throughout the processes, understanding that restoring extinct animals is hard work, and sharing in the ride when it takes us on surprising twists and turns as to what we think an animal looked like (I certainly didn’t expect to end up with such a different view of Dimetrodon when I started!).

If for no other reason than this I would recommend supporting them. I’ll have more to say about Permia (and their products - I’ve been wearing prototypes of their shirts for a couple of weeks) in another post coming soon, but if you’re interested you can check them out right now on their Kickstarter campaign. It’s well worth a look.