The lip post

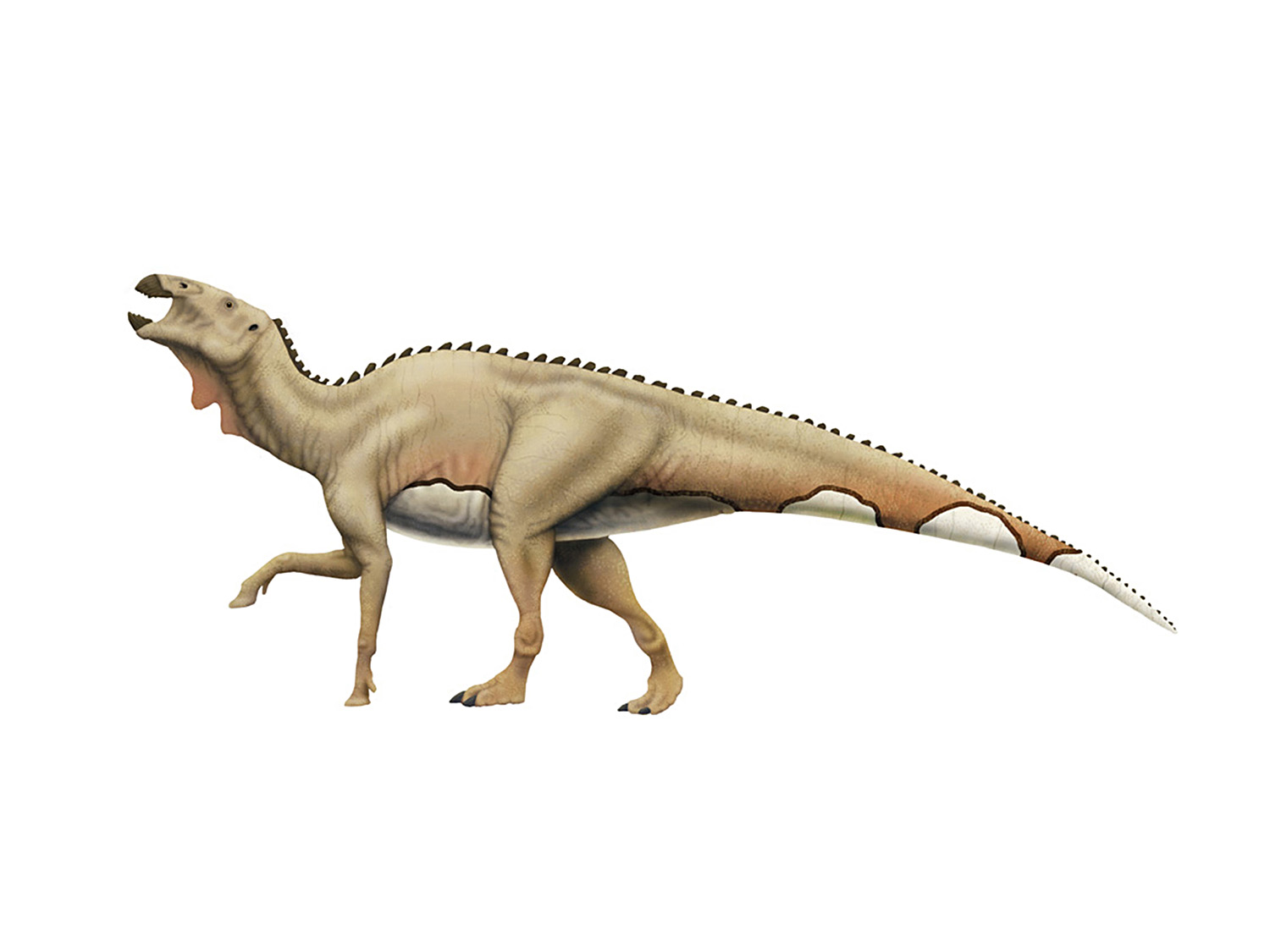

/Lippy Deinonychus. Still not a good kisser!

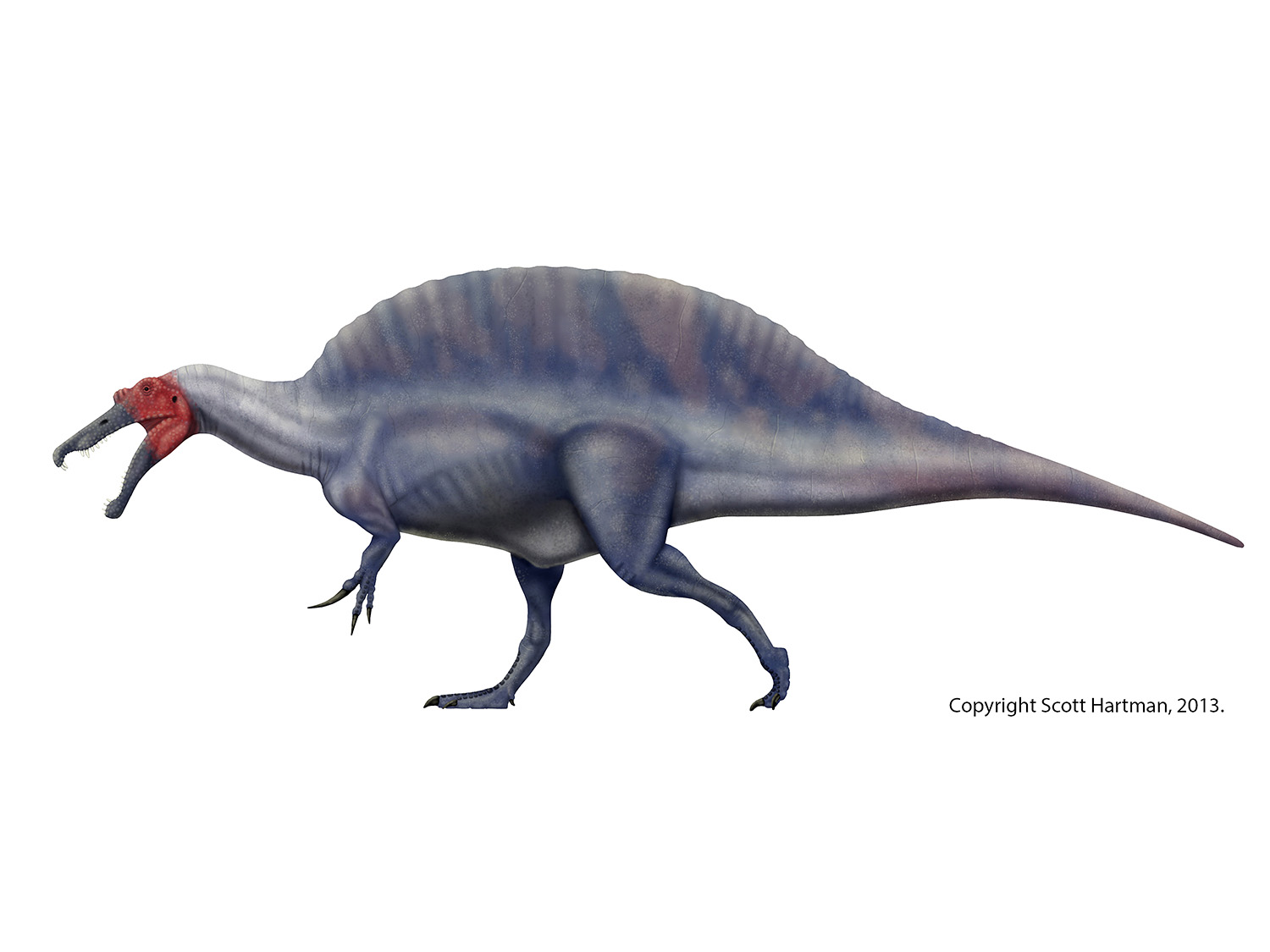

Well here we go. If you follow me on social media you’ve seen this teased, but I’m putting lips on all my non-beaked non-avian theropod skeletal reconstructions. So much for burying the lede, eh?

Ah, but some of you may be wondering why I think they had lips? And what anatomical features I’m using for adding lips and other extra-oral tissues to my skeletal reconstructions? And why I’m doing it now?

All excellent questions. Unfortunately my first draft reached word counts that really ought to be illegal on a blog, so I’ve settled for breaking this up into two separate posts. The first will cover the basics of the theropod lips controversy, the evidence that has me convinced that lips are the way to go (and so convinced I’m doing it now). Part 2 will follow in a few days and will be on the specific osteological correlates and comparative anatomy I’m using to restore them. So with that, let’s dive in:

Lips on theropods are controversial

As with any topic that is subject to debate, how controversial you find this post will in large part depend on how much you already agree with it. But beyond that I want to acknowledge that this subject lacks a scientific consensus - and not in a “we weren’t there so we can’t know for sure!” sort of way (which is often the last refuge for individuals who don’t want to acknowledge contradictory evidence), nor a “some scientists think birds aren’t dinosaurs” sort of way (that is, a debate that has a settled consensus even if you can find an outlier or two who are willing to provide quotes to the media in opposition of a widespread consensus).

No, the debate over non-avian dinosaur extraoral tissues (lips, beaks, cheeks, or the lack thereof) is one that truly doesn’t have anything approaching a scientific consensus. You may be thinking “But Scott, you said you were convinced!”, and truly dear reader, I am. But as a stem educator I think it’s important to acknowledge when when a topic lacks legitimate consensus, especially when you are trying to make a case for one side or the other.

Moreover, because this debate has a big impact on how paleoartists restore the most popular, awesomesaucy of all extinct beasts (not to mention scientific interpretations of them) it has naturally proliferated across not just scientific papers, but paleoart blogs, popular articles, and gray literature. Bob Bakker was arguing for lizard-like lips on theropods in the pages of The Dinosaur Heresies back in the mid-1980s, an interpretation also championed by Greg Paul. Tracy Ford has spent a lot of time arguing the opposite in the pages of Prehistoric Times, and perhaps most recently a paper describing Daspletosaurus horneri (and coverage of the story) has went beyond the description of a new species to make peer-reviewed arguments claiming that at least tyrannosaurs were lipless like alligators.

So how is a person to decide? Let’s try to break this down.

The case against theropod lips

A lipless Daspletosaurus horneri.

Two main arguments have been advanced to support the idea of a more alligator-like lack of lips in theropods - one based on extant phylogenetic bracketing, and one based on nerve openings and bone texture on the bones around the mouth (the dentary, maxilla, and premaxilla). The extant phylogenetic bracket argument is easy to understand - living theropods (birds) lack lips, as do their closest living relatives (crocodilians), so the default interpretation is that non-avian dinosaurs also lacked them.

The anatomy argument is based on nerve openings and bone texture in the face, (so far mostly in tyrannosaurs). The authors of the D. horneri paper (Carr, et al.) looked closely at the texture of the bones of the skull and attributed a wide range of skin types to them, including keratinous horn-like material, and large and small scale patterns. Specifically relevant for us they interpreted the rugose patterns on the maxilla as being similar to the textured snouts of crocodilians. They, as well as Tracy Ford argue that the foramina (small holes for nerves and/or blood vessels) on the snout and jaws of tyrannosaurs may have made them with highly touch-sensitive, meaning that the nerve openings were to support tactile perception, not lips.

There are also occasional arguments about particularly large-toothed theropods (like Ceratosaurus or Tyrannosaurus) that implies their teeth are simply too large to be enclosed in lips…but that will have to wait until the next blog post. Even with just these main arguments, if the default assumption is lipless theropods and the texture/nerve openings on the snout and jaw support some other use than lips…why would anyone believe otherwise?

The case for theropod lips

First, while the following are my own views on the subject I would be remiss not to acknowledge the many others who have tackled the pro-lips argument before, and anything I’ve read undoubtedly has played a role in my thoughts on the subject. As I mentioned above Bob Bakker and Greg Paul have long argued for immobile, lizard-like lips on theropods, and Greg recently updated his case in the Fall edition of the paleoart/collectibles magazine Prehistoric Times. On the interwebs Mark Witton and Jaime Headden have also made extensive blog posts on the subject. I apologize to others I’ve missed or simply didn’t read. Now then, I want to make clear that in my estimation there are serious problems with the current case against lips.

First off, we need to discuss extant phylogenetic bracketing. The important thing to keep in mind about phylogenetic bracketing is the process is not evidence in and of itself - it’s instead a way of establishing how high the burden of evidence should be when inferring soft-tissue anatomy in extinct organisms. For example, if all of your living relatives have some soft-tissue feature you are investigating, and a fossil species has the same underlying bony anatomy it’s what is called a Type I inference. A Type I inference is the safest form of inference, and requires the lowest burden of evidence (e.g. the fact that everyone has a similar-looking structure) to make your case. Alas, birds and crocodiles don’t between them have remotely the same type of mouth anatomy (with birds having toothless beaks, and crocs having no beaks but teeth set in lipless jaws), nor do they have the same underlying mouth anatomy, bone texture or nerve/blood supply openings on their faces. So neither side of the theropod lips debate gets to claim a Type I inference.

A Type II inference is where only one set of living relatives shares similar anatomy with the fossil species you are looking at. Since your fossil species doesn’t have the luxury of having the same anatomy as both of it’s closest bracketed living relatives it naturally requires a higher burden of evidence to establish that the fossil species in question closely matches one or the other condition. We can safely rule out avian toothless beaks for most non-avian theropods, but we need to at least consider whether toothed theropods share enough anatomical similarity with alligators and crocodiles that is associated with liplessness to justify a Type II inference. If not (e.g. if most theropods had lips) unlike either birds or crocodiles it’s a Type III inference, and therefore requires the highest burden of anatomical evidence. In other words, the anatomical evidence has to be pretty strong to justify shifting the interpretation from a Type II to a Type III inference.

American Crocodile credit Daderot Public Domain, T. rex maxilla photo is my own

But non-bird theropods clearly have very different anatomy from from living crocodiles and alligators, in almost every way you can examine their oral and facial anatomy. If you look at how the edge of the mouth is formed, crocs have upper tooth rows that are set in from a gently curving mouth edge (because that edge doesn’t support lips) and their lower teeth often interdigitate between or even protrude to the outside of their upper teeth (their lower teeth also frequently point laterally or anteriorly…because there are no lips to get in the way). That doesn’t look anything like most non-avian theropod tooth rows, which are set close to a sharp-rimmed outer edges of the mouth (the kinds that lips could grow from) and their lower teeth are either inline with or set to the inside of the upper tooth row (and their lower teeth are not oriented sideways or otherwise angled into the area where lips would be). I’ve highlighted some of these differences in the adjacent photos.

Given that basically all of the anatomy associated with liplessness in crocs is absent (and generally in direct opposition) it would seem a Type III inference is easily made from the preponderance of evidence. I would also argue that this shouldn’t be unexpected once you take a broader phylogenetic look at the distribution of lips in tetrapods (land vertebrates). Lips are extremely common in tetrapods. Mammals, living amphibians, tuataras and lizards/snakes all have lips, which suggests having lips is actually the default condition while losing lips is the less-common and more specialized scenario. Note that both amphibians and lizards share with non-avian theropods similar edge-of-the-mouth and tooth orientation anatomy as described above, further strengthening the connection between lips and mouth anatomy.

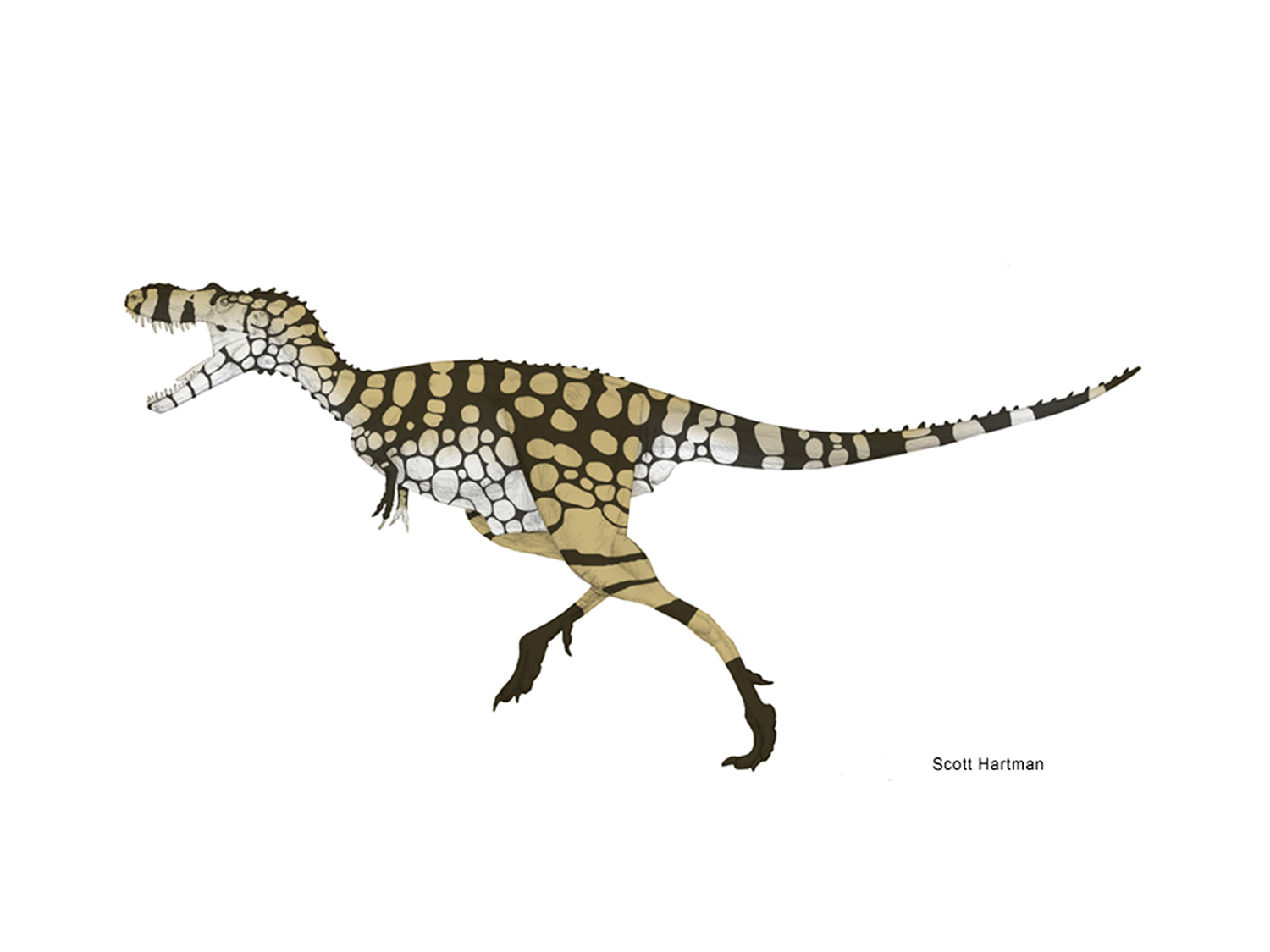

But what of the foramina and textured surface of facial bones in tyrannosaurs? This has been addressed in greater depth by another Mark Witton blog post as well as by Duane Nash, but in short while Carr and coauthors do a lot of good work correlating bony surface textures to different skin types on the face of D. horneri, I don’t believe they make a convincing case that the highly sculpted facial texture of crocodilians (which Duane points out is seen in several other other aquatic predators) is similar to the texture seen on theropod facial bones, even in tyrannosaurs (whose facial bones tend to be more textured than most theropods). That crocodile-like texturing also fails to show up on the lower jaw of theropods (unlike crocs), where there is instead a row of foramina (holes) that seem to gently curve down where the largest upper teeth would go when the mouth closes - if this supported the bottom of the lower lips it would form a tooth pocket for the upper teeth. Needless to say this foramina pattern is not seen in crocodilians. In theropods with particularly large differences in upper tooth length (as in tyrannosaurs, which have large maxillary teeth but much smaller premaxillary teeth) the change in the depth of the tooth-pocket on the mandible can be quite striking (see photo below).

MOR 980 mandible - foramina highlighted in red on the bottom image

I find this comparative anatomy compelling on its own. But in the last decade there was also an excellent quantitative investigation of facial foramina by Ashley Morhardt. For her masters degree Ashley statistically analyzed foramina in living tetrapods, testing for correlations with their extra-oral soft-tissue structures, and then comparing the results to the foramina of dinosaurs.

Unfortunately, as often happens her Master’s work hasn’t been published yet in a peer-reviewed journal (by the way, Ashley’s PhD work researching brain cases and paleoneurology at the Witmer lab has also been top notch, but that’s not today’s topic!). But Ashley’s Master’s thesis is online for anyone who wants to read it, and she presented her results at several scientific conferences. Since it’s unpublished I won’t detail the entire thing here, but it definitely supports fleshy extra-oral soft-tissues in dinosaurs rather than crocodile-like lipless smiles.

In summary: When looking at tetrapods as a whole, having lips is the normal condition while losing lips is a weird/specialized condition. Most non-avian theropods obviously don’t the same oral anatomy as their beaked living avian descendants, but they just as clearly lack the anatomical features we see in lipless living crocodilians - their bottom teeth are not oriented like crocs, the edges of their mouths look very different, the textures on their facial bones are not the same, they appear to have lip-pockets on their lower jaws and when modern quantitative techniques are applied to toothed theropod foramina they match up with animals that also have lips, not with crocodiles or birds. There may not be a scientific consensus yet, but with the currently available evidence I consider lipped theropods to be the overwhelming favorite.

Yeah, but why now?

This is actually a trick question - I started making these changes almost a year ago, and started making them in earnest about six months ago. I’d hoped to write about it over the holiday break, but I ran out of time. What can I say, it takes time to make these updates! Even as this post goes live I’ll only have about ~50% of my skeletals updated in the theropod skeletal gallery. How best to portray the lips on my theropod skeletals is something I’ve been actively wrestling for a while. I had previously convinced myself that while most theropods had lips, maybe I didn’t have to go back and change all of my skeletals if the lips were small enough and/or flexible enough to move out of the way in side view. But getting a close-up look at other lipped reptiles showed this was very unlikely, and moreover many paleoartists (including myself in the past) had followed the insufficient lips on my skeletals in life reconstructions, leaving those theropods in a state of halfsies - not quite a crocodile smile, but not a plausible set of lips either. So it was time to update.

So, white teeth?

As some alert readers guessed, one of the reasons I wrote my post on the problem with outlines in scientific illustrations was because the teeth are going to be impacted. In the past I’ve only drawn theropod teeth in black, to avoid exaggerating their size. Because I’m switching to lipped theropods, most or all of their teeth are going to be behind the lips in side view - so if I left them black they would essentially be invisible. That won’t work, so I’ve had to go back and illustrate them all in white. That works fine for smaller-toothed theropods, but some of the larger-toothed skeletals still have the tips of their teeth poking out past the lips. Which puts me in the very uncomfortable position of having to place an outline around the teeth where they stick out, potentially exaggerating the size of the teeth. To all the paleoartists out there, please resist the urge to make the teeth extend all the way to the outside of that black line - they weren’t that large in life!

OK, so what did theropod lips look like?

Its bite is definitely worse than its bark. Credit Anna Yu via Science Daily

Even if you now agree that lips are by far the most likely condition for theropods there is still the problem of how to go about restoring them. How large were the lips? How visible would the teeth have been in life? Obviously we can rule out muscular, mammal-like lips but after that there’s still a decent range of variation to choose from. This will be the topic of my second lips post, but as food for thought (or something to worry about) check out this image of a Komodo dragon with its mouth wide open in a threat display. See any teeth? Neither do I, but I assure you they’re there, they’re just totally hidden behind lips and gums.

This post was brought to you by Permia

This post is supported by the good folks at Permia. Permia products are the result of self-described paleo super-fans collaborating with paleontologists and artists to create uniquely high-quality clothes and collectibles. I can tell you from personal experience that they never compromise on scientific accuracy, and now they have been so generous as to support posts on general interest paleontology topics. Check them out here: www.permia.com