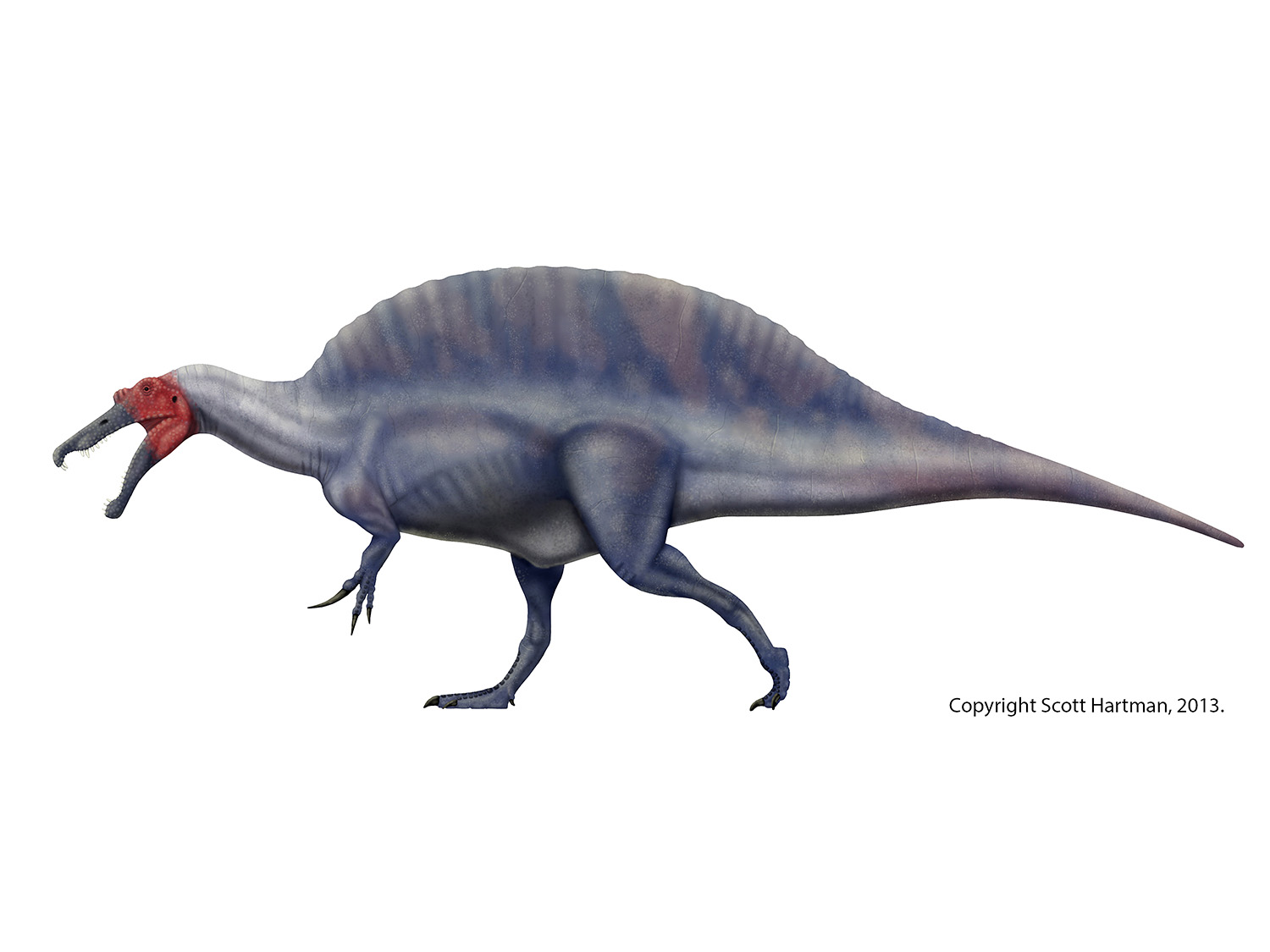

The road to Spinosaurus II: Known unknowns

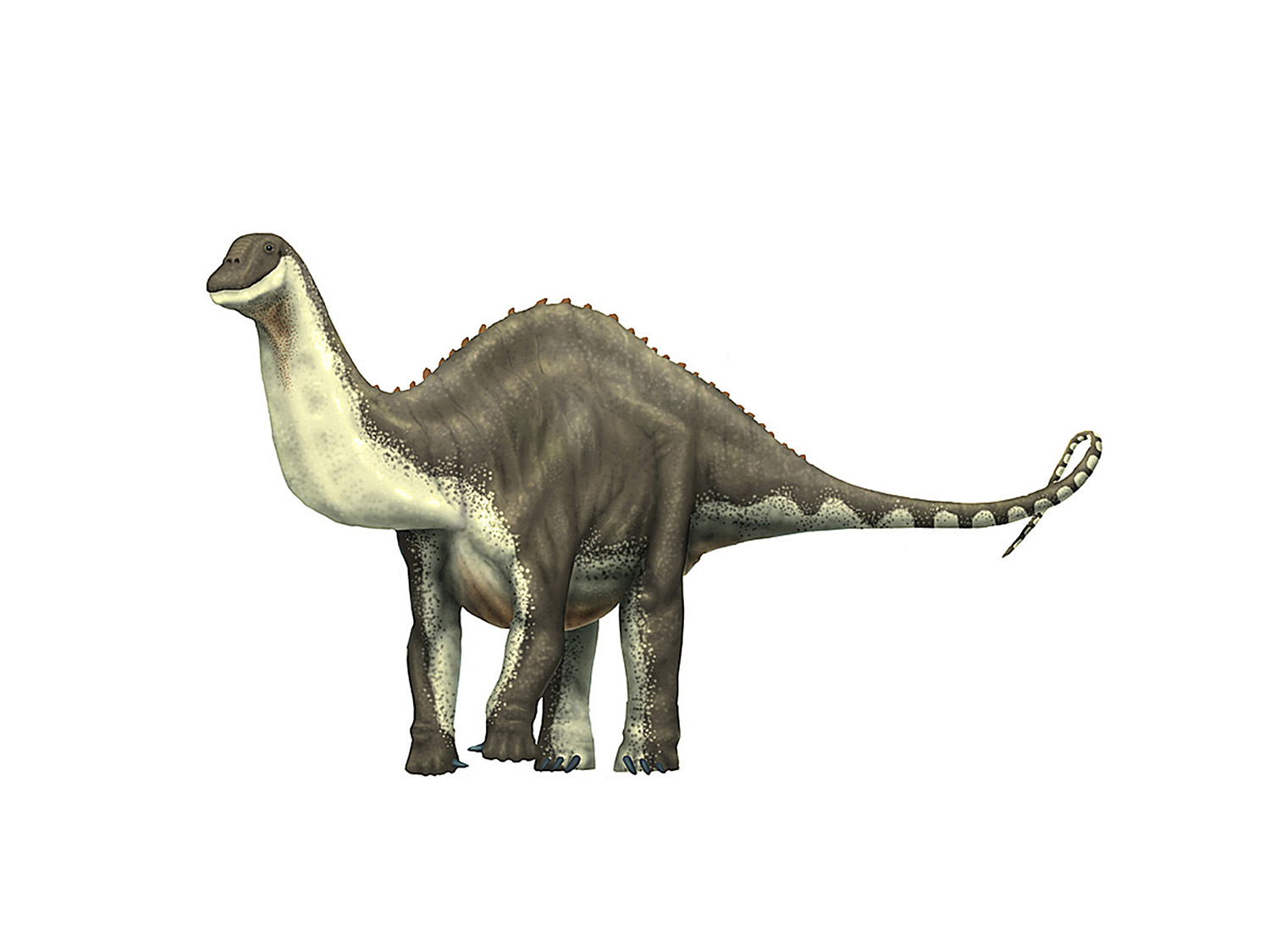

/A rigorous version of FSAC-KK 11888, after the proportions and bones presented in the 2014 description. Yes, I know there’s a new tail now, bear with me we’re getting there…

When trying to restore the proportions of Spinosaurus, the elephant in the room is obviously FSAC-KK 11888. When described in 2014 it was purported to resolve most of the mysteries in understanding the proportions and ecology of Spinosaurus, shifting it from a JP3-style large terrestrial, bipedal, carnivore with a rounded sail to a knuckle-walking, aquatic pursuit eater of fish with an M-shaped (AKA sigmoidal or a sail with two peaks). Of course there’s been some controversy about each of those claims, and I will weigh in on them in due course. But today I want to look at so-called M-shaped sail, as it has been uncritically repeated on many dozens (if not hundreds) of illustrations since 2014, despite having literally zero evidence in favor of it.

If you take a look at the rigorous skeletal drawing of FSAC-KK 11888 at the top of the article, I hope you begin to see the problem. This may come as a surprise to some, as a prominent image in the original paper (Ibrahim, et al., 2014, Figure 2) shows an impressively complete skeletal based on the “known bones” of Spinosaurus. Alas, in reality the FSAC specimen was not very complete (although most of a tail has been discovered since). To be fair, a full reading of the caption for Fig. 2 explains their image is based on “…FSAC-KK 11888, referred specimens, and drawings of original bones…” (emphasis mine). And in the supplemental data there is a more useful image that uses different colors to indicate the various specimens used to fill out their composite (Fig. S3; the use of highly saturated red and orange can make it somewhat difficult to tell the FSAC material from the type material, but other contemporaneous images, e.g. one from a National Geographic article at the time did an even better job of labeling the various specimens).

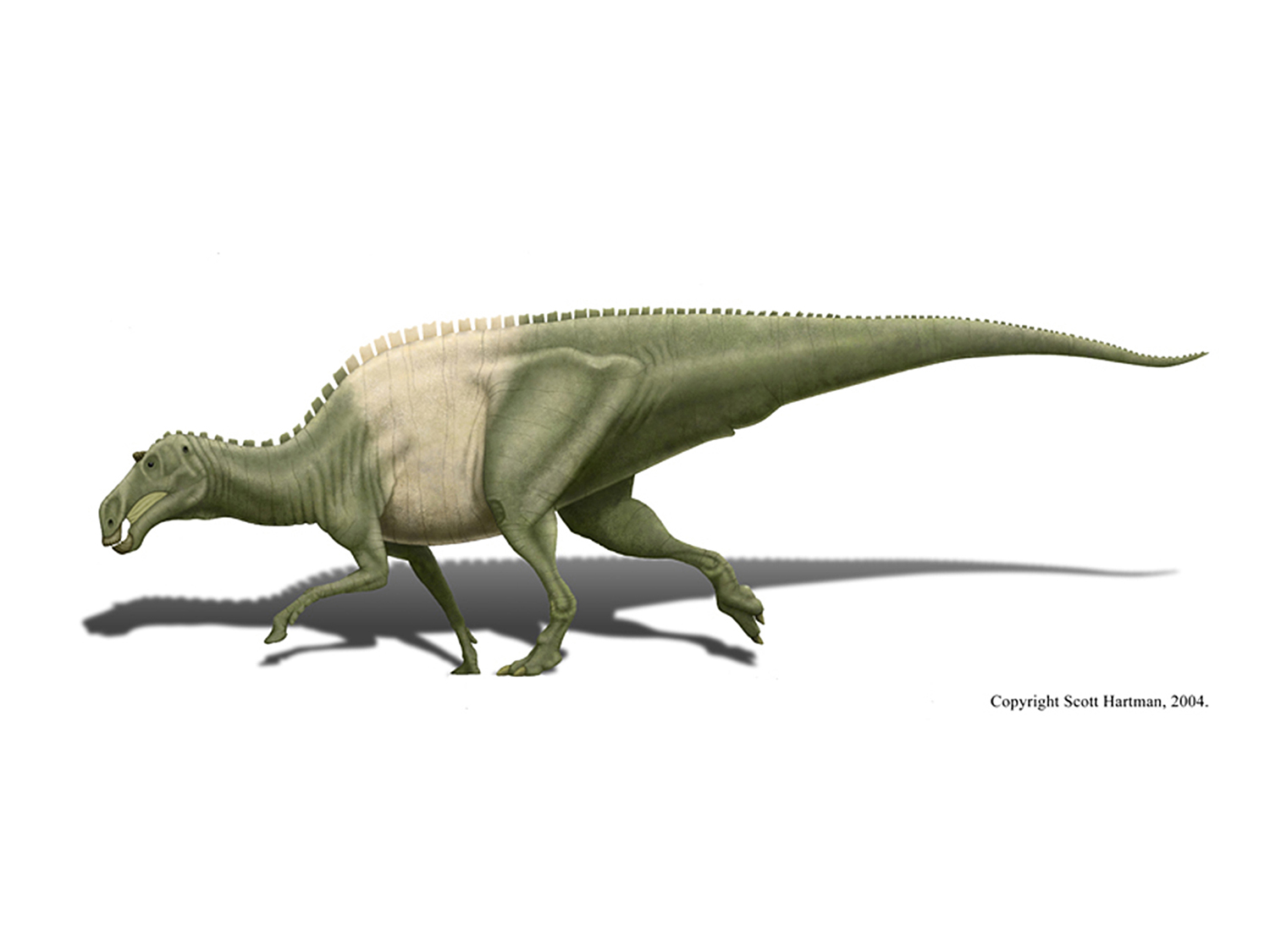

Photo modified from Smith, et al., 2006. Red shows broken edges on neural spines.

The important thing for this post, however, is the FSAC specimen does not have any complete dorsal neural spines*, and the spine bits are not attached to specific centra, so their position can only be roughly known. The type specimen had more complete neural spines, but most were still broken at the top, and their positions in the back are likewise not known with precision (see Smith, et al., 2006…unfortunately behind a paywall, and blog posts by Jaime Headden, 2011 and Andrea Cau in 2008 for pre-FSAC takes on neural spine position that differed from Stromer’s original designations). The type specimen was famously blown up during WWII, so we cannot further investigate them beyond Stromer’s publications and some rare photographs.

So… how did the Ibrahim, et al. sigmoidal sail-shape come to be? That’s a good question, since there are no FSAC neural spines from the mid-dorsals on back in their reconstruction. And while there are good reasons to think some of the type specimen’s neural spines did fill in that space, those had broken edges at the top so we don’t know how tall they were in life. The simple fact is that neither specimen has the data to suggest the sigmoidal shape that launched this paleoart meme.

Before you think “well, maybe by combining them we can infer that shape” let me just stop you right there. First, even if you accept both specimens are the same exact species (and they are clearly close relatives at the least), we know almost nothing about potential variation between individuals, during ontogeny, by sex, or across geography or time. Moreover, there is still the issue that we simply don’t have posterior dorsal neural spines from FSAC, and we don’t know how long the relevant neural spines were in the type, since they were broken at the top.

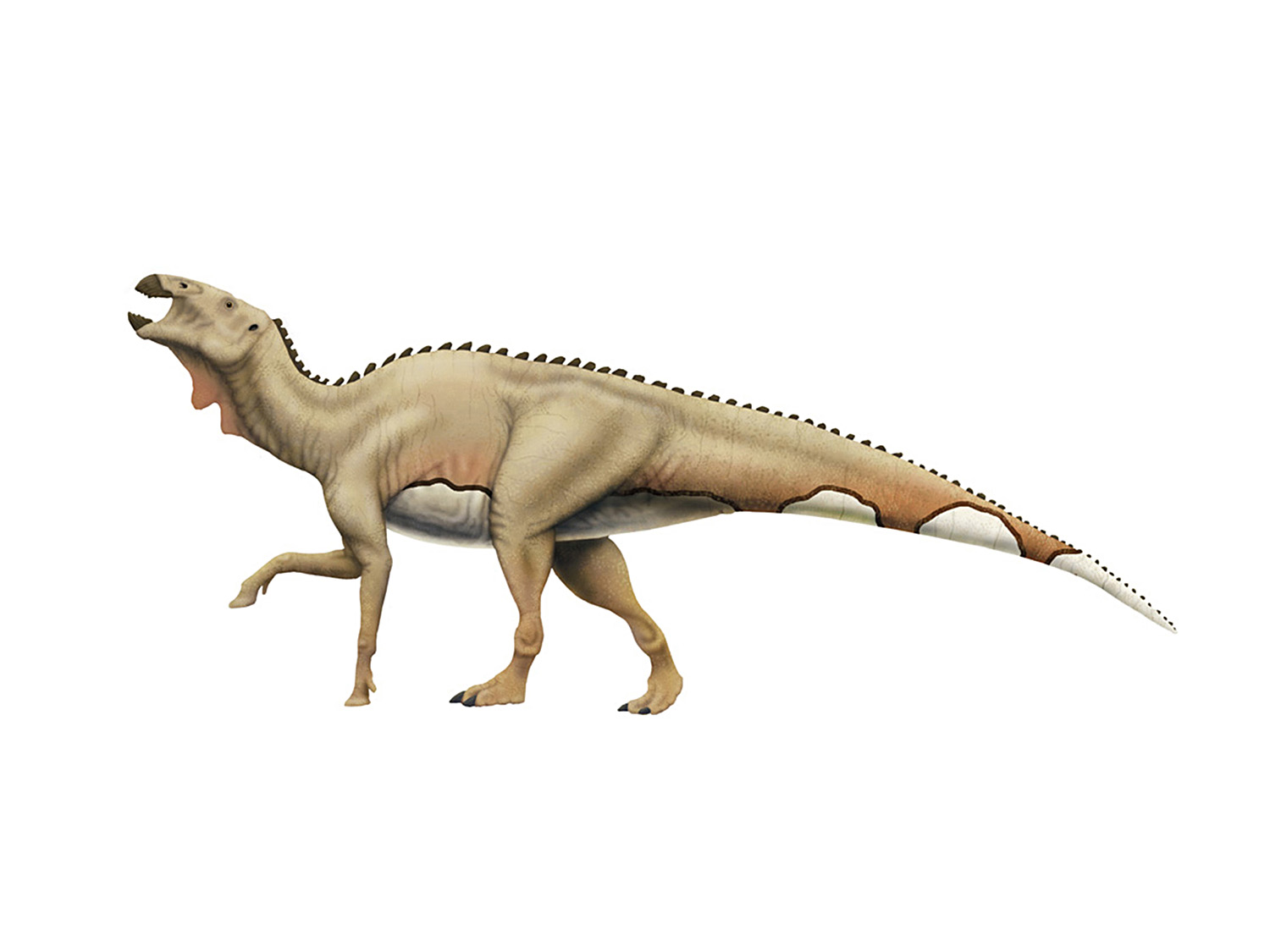

It’s wouldn’t be my first choice of sail shape, but it’s fine as far as the data is concerned.

So does that mean the sail shape from the Ibrahim, et al. papers is wrong? At this point we can’t say. We also can’t say it’s wrong for the sail to have been rounded more like traditional reconstructions. For that matter, we don’t know about sacral neural spine height, and even the anterior caudal neural spines in the new FSAC tail appear incomplete. For all we know there could be a sharp peak in the middle of the back and then an exaggerated Ichthyovenator-like dropoff and recovery over the pelvis that tapers off over the anterior-most caudals. The point is not that Ibrahim, et al. did anything wrong with their speculative sail-shape in their papers - it’s absolutely one possibility given how much data we are missing. But paleoartists (and those who like paleoart) should realize it’s speculative, and you should not feel constrained to imitate it. Spinosaurus sail shape is truly a known unknown at this time.

This post was brought to you by Permia

Why? Because in addition to making fantastic paleontology-themed products and apparel, the good people at Permia like Spinosaurus too!

Works cited

Ibrahim, N., Sereno, P. C., Dal Sasso, C., Maganuco, S., Fabbri, M., Martill, D. M., ... & Iurino, D. A. (2014). Semiaquatic adaptations in a giant predatory dinosaur. Science, 345(6204), 1613-1616.

Smith, J. B., Lamanna, M. C., Mayr, H., & Lacovara, K. J. (2006). New information regarding the holotype of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus. Journal of Paleontology, 80(2), 400-406.

* I realize one of the neural spines looks fairly complete in my rigorous skeletal at the top. In their subsequent 2020 paper describing the new Spinosaurus tail Ibrahim, et al., provide more detailed information on completeness in their Extended Data Fig. 3. This indicates that none of the preserved neural spines are anything like complete, and also shows e.g. less of the ilium was known than implied in their 2014 supplement. But I wanted to stick with what was provided in 2014 rather than cherry-pick from the new 2020 completeness data, so I didn’t manipulate the neural spine in the top image to make a point.