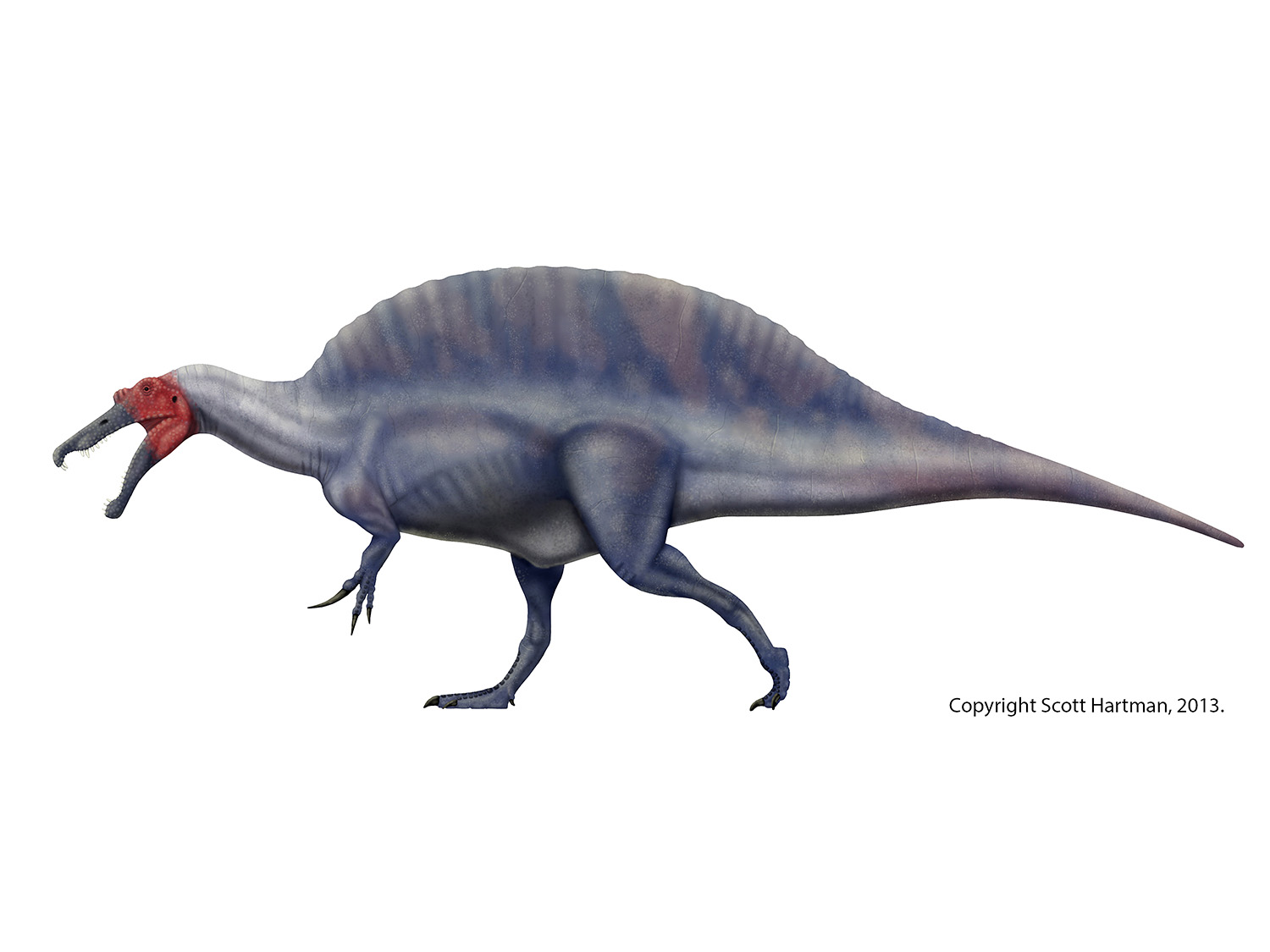

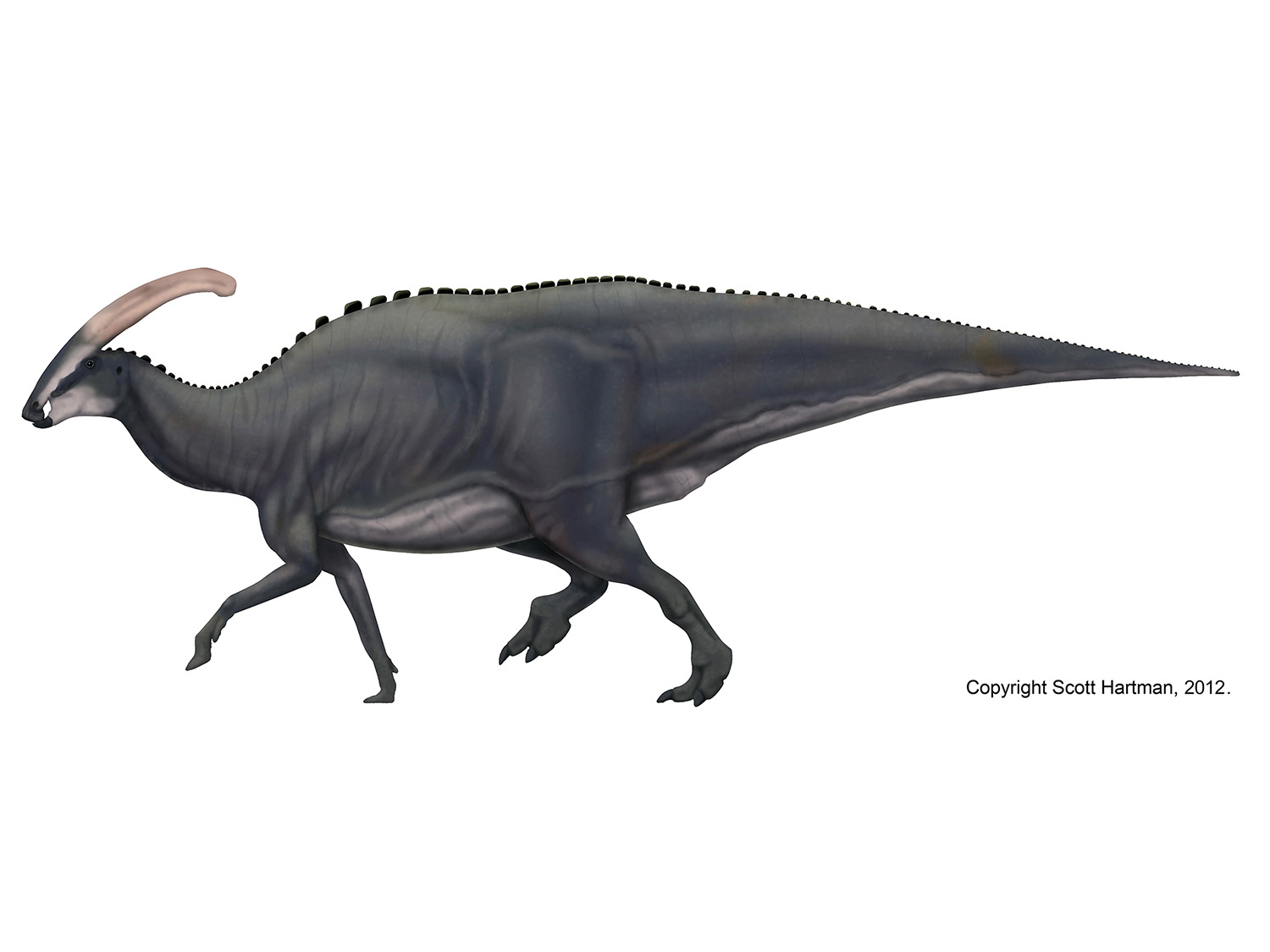

The road to Spinosaurus I: Megalosaur skulls

/A few years back I wrote a couple of essays about Spinosaurus, looking at the most recent specimen (FSAC-KK 11888) and what could be said about the proportions and habitat of Spinosaurus. Ultimately I wasn’t able to come to a firm conclusion, and decided I would work from the ground up to create a new skeletal.

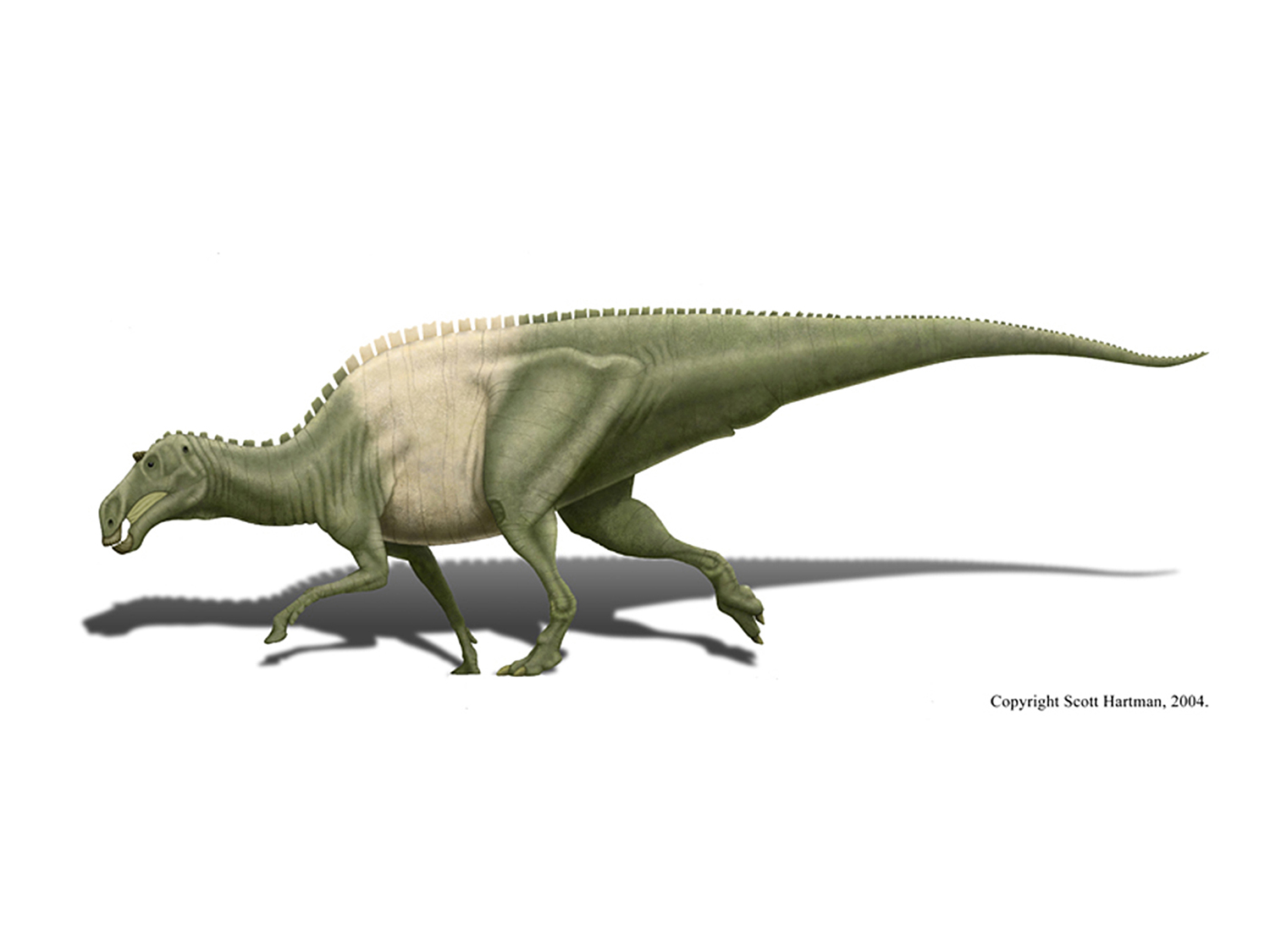

The restored skulls of Eustreptospondylus, “SAH” is mine, “GSP” is copyright Greg Paul (from his 1988 Predatory Dinosaurs of the World).

It has been slow going since then, as I was preoccupied with finishing my PhD, publishing papers on other topics, and teaching courses at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. But I’ve kept whittling away at it, and today I want to start laying out my thoughts on this challenging topic. Starting phylogenetically broadly and working towards El Spino, here is a quick look at the proportions of megalosaur skulls.

Historically megalosaurs have been known from less than ideal remains, including a lack of articulated skulls. With fairly scrappy remains to rely one, they have traditionally been restored with tall, blocky, vaguely allosaurish skulls. Greg Paul’s take back in his venerable 1988 Predatory Dinosaurs of the World (first figure) was not nearly as short or blocky snouted as most contemporary examples - it was common to restore Eustreptospondylus with an almost ridiculously short (front to back) and tall skull, an interpretation no doubt inspired by the original attempt at a physical reconstruction (a photo of which can be seen on David Hone’s blog here). The influence was pervasive for decades, and similar variants can still be seen in a Google Image Search today. Somewhat more recently megalosaur skulls have been restored with longer snouts, but ones that are tall and blocky (and sometimes quite wide), including the Eustreptospondylus model used in the Walking With Dinosaurs BBC special. I have been guilty of this myself, restoring the skulls in my Megalosaurus and Marshosaurus skeletals in the tall and blocky tradition.

The more elongate skull of Torvosaurus, as seen in the new Cincinnati mount. Photo Copyright Larry Witmer Lab.

This view of megalosaur skulls made nesting spinosaurs (and their long, narrow skulls) within megalosaurs seem strange*. Of course there’s nothing wrong with groupings that feel superficially counter-intuitive - sometimes subgroups are quite different in proportions from their relatives. Giraffes and whales, for example, are just as much artiodactyls as deer are despite having very different proportions.

But about two years ago as I worked up my Eustreptospondylus skeletal (based on the excellent redescription by Sadlier, et al., 2008), I was struck by how long and slender the skull was. Shortly after that I also got to see the newly reconstructed Torvosaurus skull that has gone on display in the Museum of Natural History & Science in Cincinnati, which also features a longer and (mostly) lower snout than past reconstructions. Having seen the material the remains are based on, I went back and checked the assumptions in my original skeletal and realized they would absolutely fit together this way - I had been working from the tall & blocky historical impression previously.

The more complete skull of Dubreuillosaurus definitely has a long and low skull; and it’s possible the skull was even longer than most current reconstructions, as the maxilla contacts with the lacrimal and jugal are not preserved, and the broken lower portion of the maxilla is shoved rather far back into the incomplete jugal region. Comparing Dubreuillosaurus to Eustreptospondylus, and their broad similarities with the less generously preserved megalosaur skulls and it looks like having long and low snouts was a common feature in the group. To that end I have reworked my skeletals of Torvosaurus, Marshosaurus, and Megalosaurus to better match their relatives, and added Eustreptospondylus to the Theropod skeletal gallery.

Of course none of these skulls is as specialized as what we see in spinosaurs, but with stout thumb claws and long, low snouts megalosaurs no longer seem such a weirdo home* for spinosaurs. So that’s the broad context, but what about non-Spinosaurus spinosaurs? More soon!

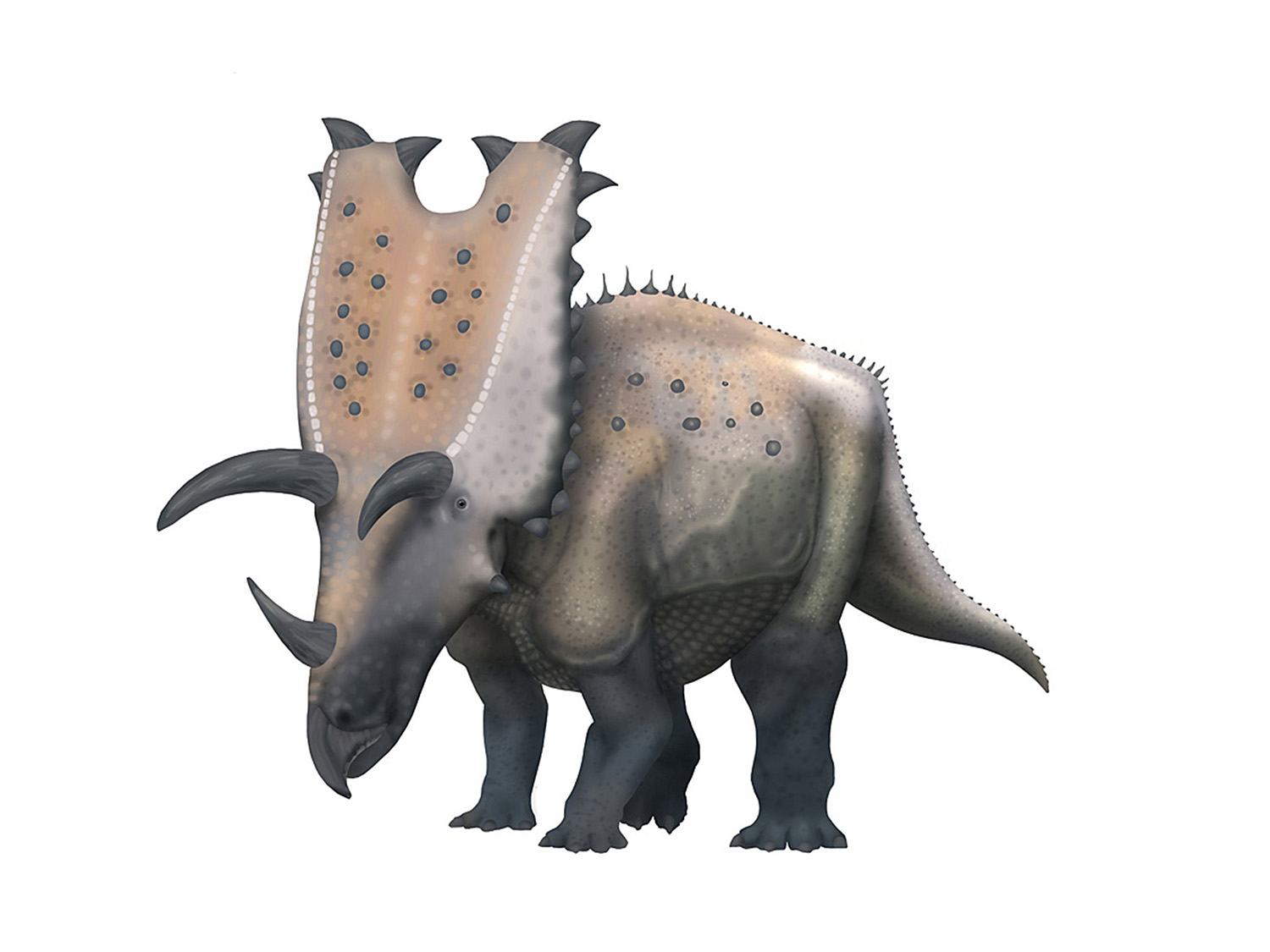

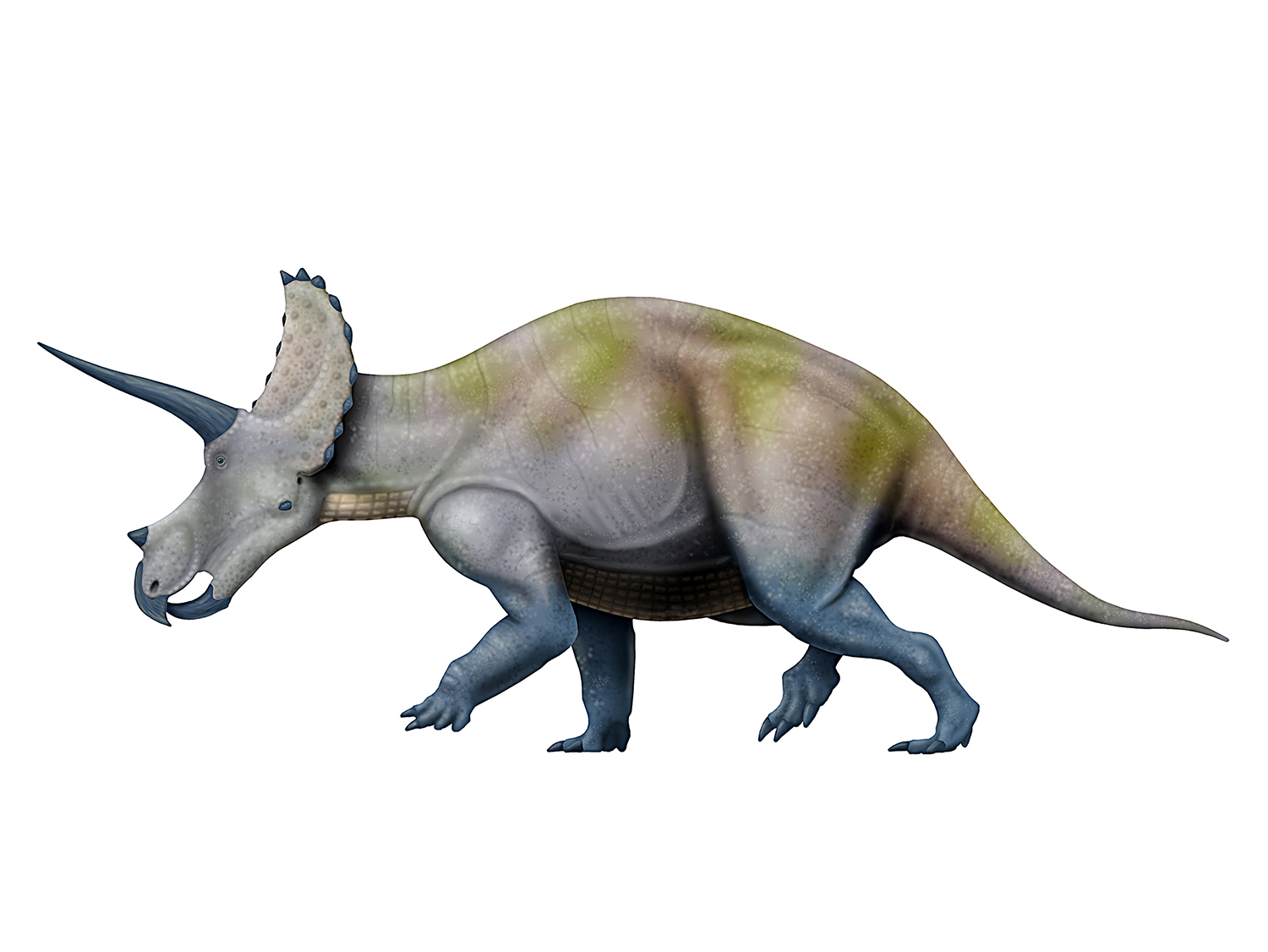

This post was brought to you by Permia

With their attention to detail, good eye for color design, and high quality materials the good folks at Permia produce some of the best paleo-themed merchandise out there. Go check them out!

* A 2019 paper by Rahut & Pol has created some disagreement about whether traditional megalosaurs form a single monophyletic group, or are actually a paraphyletic grade theropods below allosaurs. This is the sort of thing that takes lots of new studies (and therefore time) to resolve, but if if spinosaurs and other “megalosaurs” are a grade much of the above discussion still holds.