Dinosaurs didn't twerk, err....Part 2?

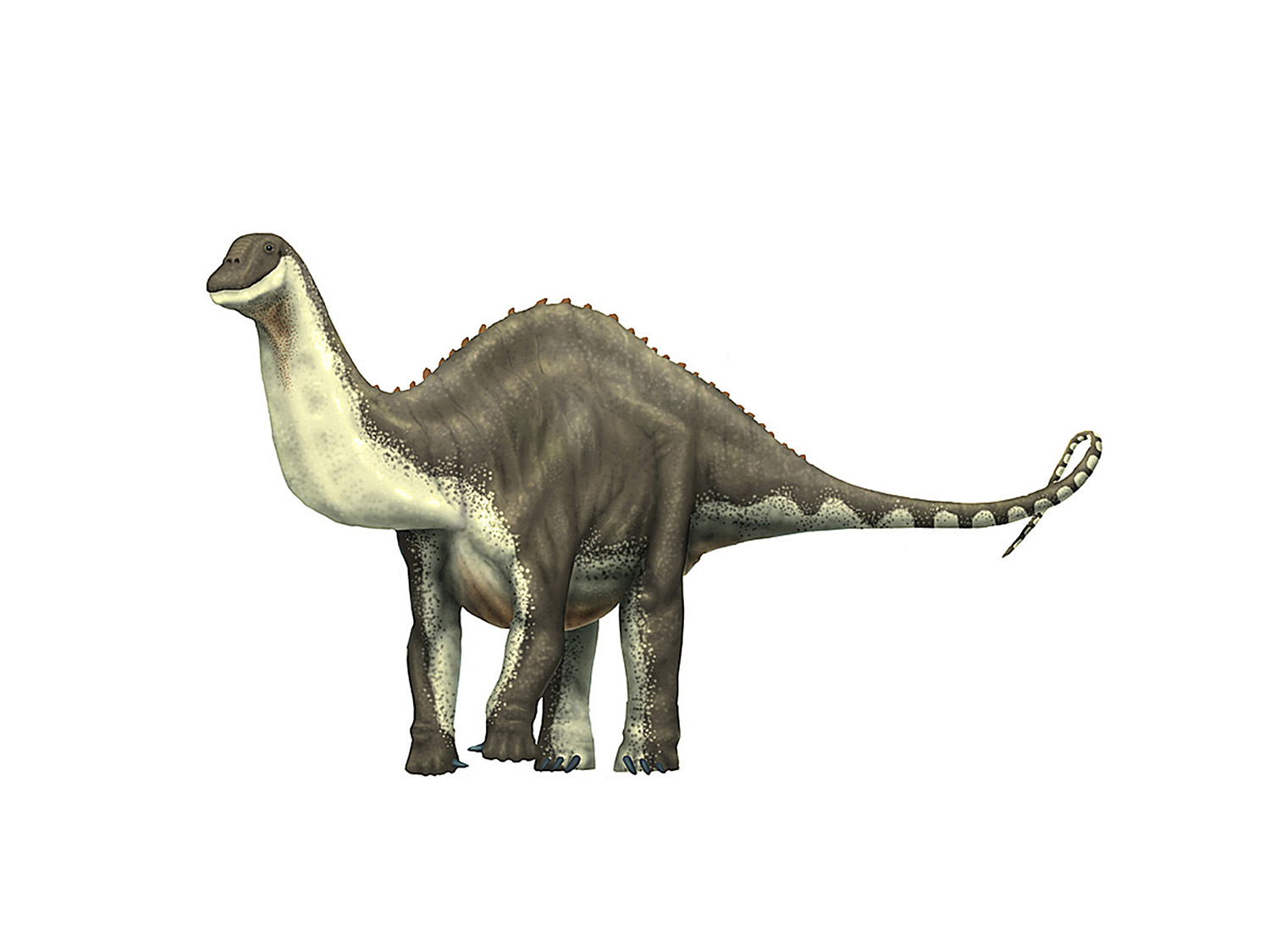

/Apatosaurus louisae thinks things are “looking up”

No, you didn’t miss Part 1 of this series (nor did you miss a follow-up to The Lip Post, it’s coming eventually!). Going back to the end of 2018 I had intended to do a two-part post about tails, limb-retractor muscle function, and posture. Part 1 was supposed to be about hadrosaurs (as a follow up to The Hadrosaur Repose from the same time period), and part 2 was going to be about sauropods. Obviously I never quite got there!

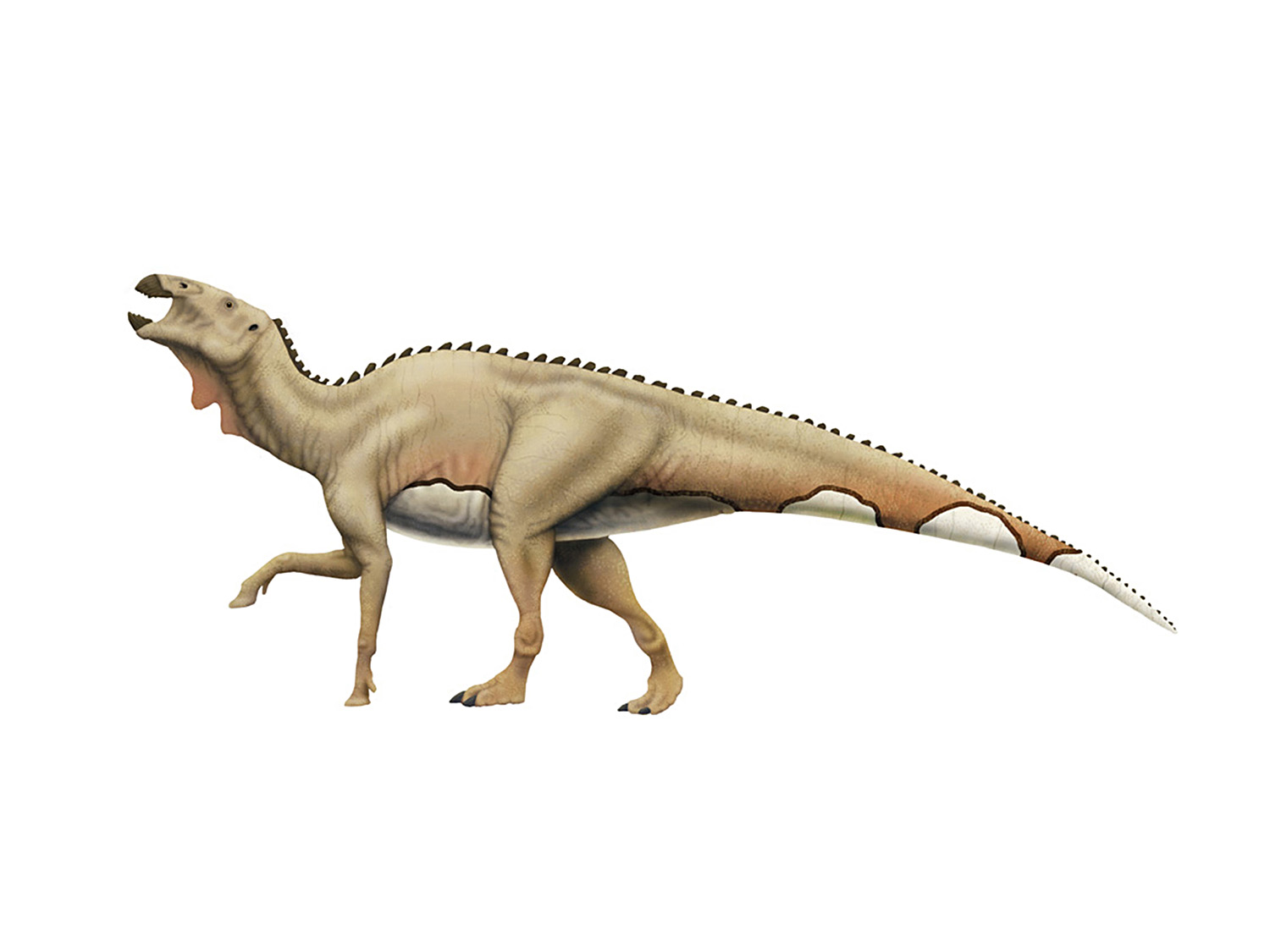

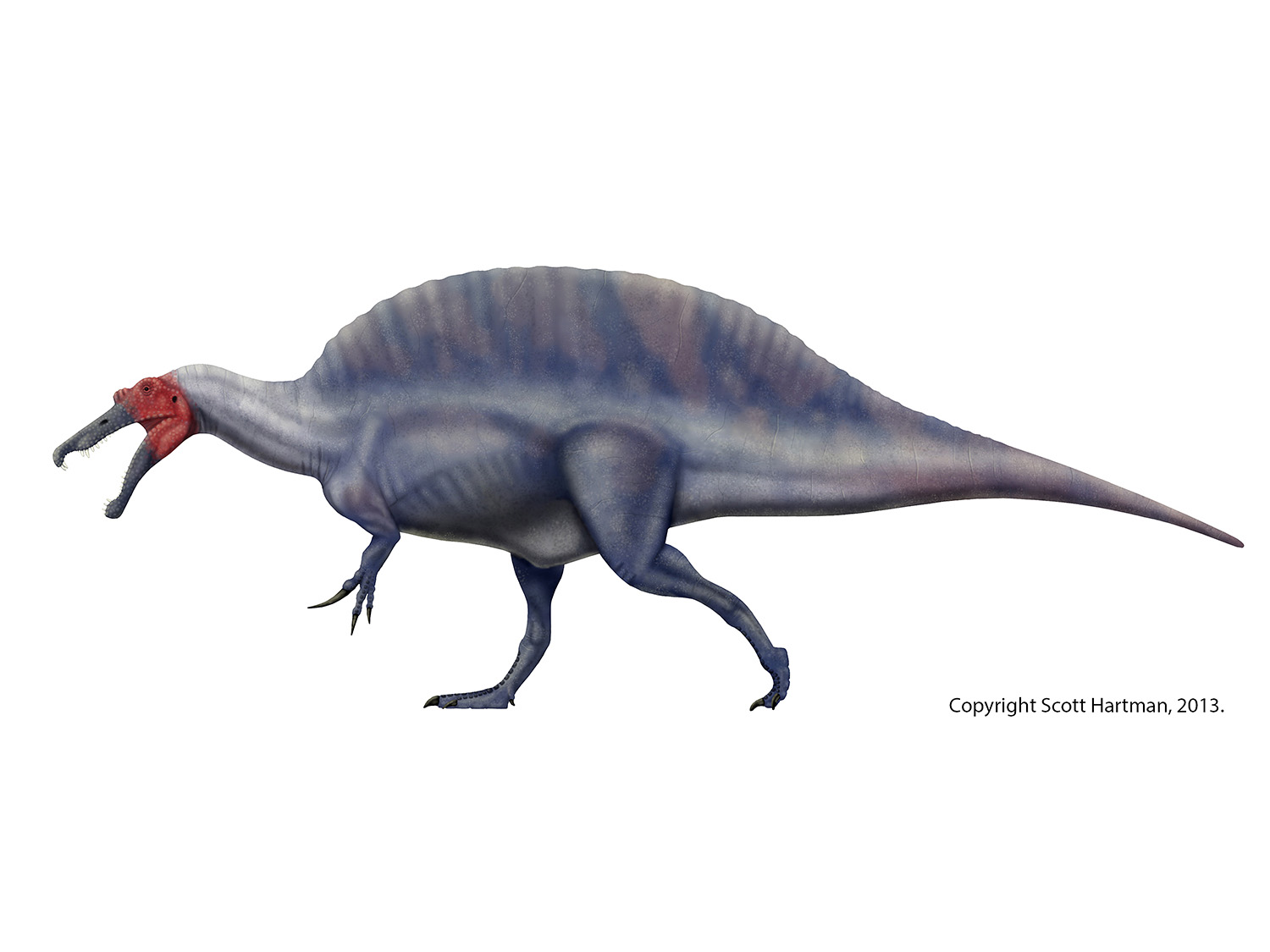

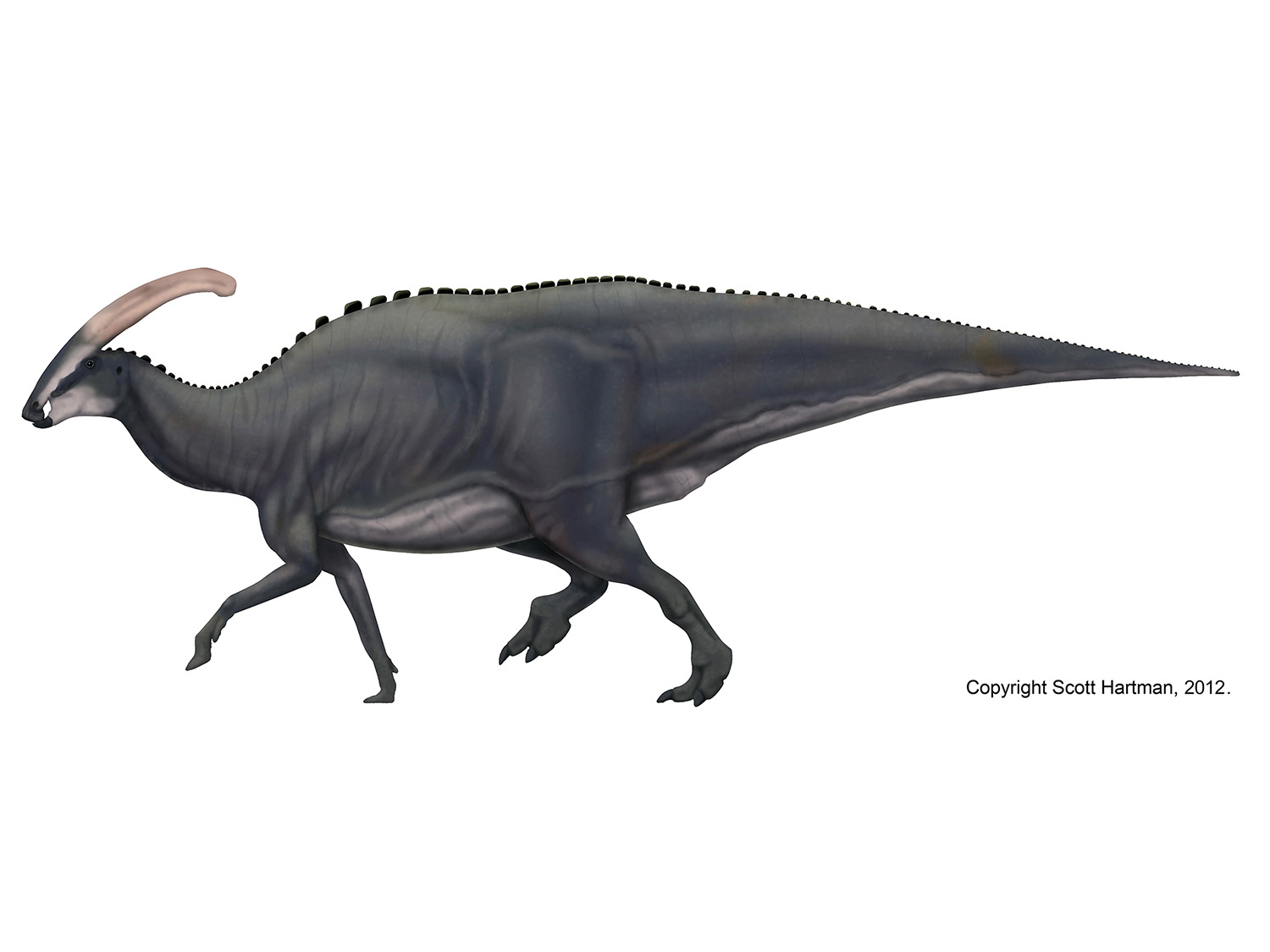

Edmontosaurus wasn’t shaking it’s tail up in the air either. Well, most of the time anyway.

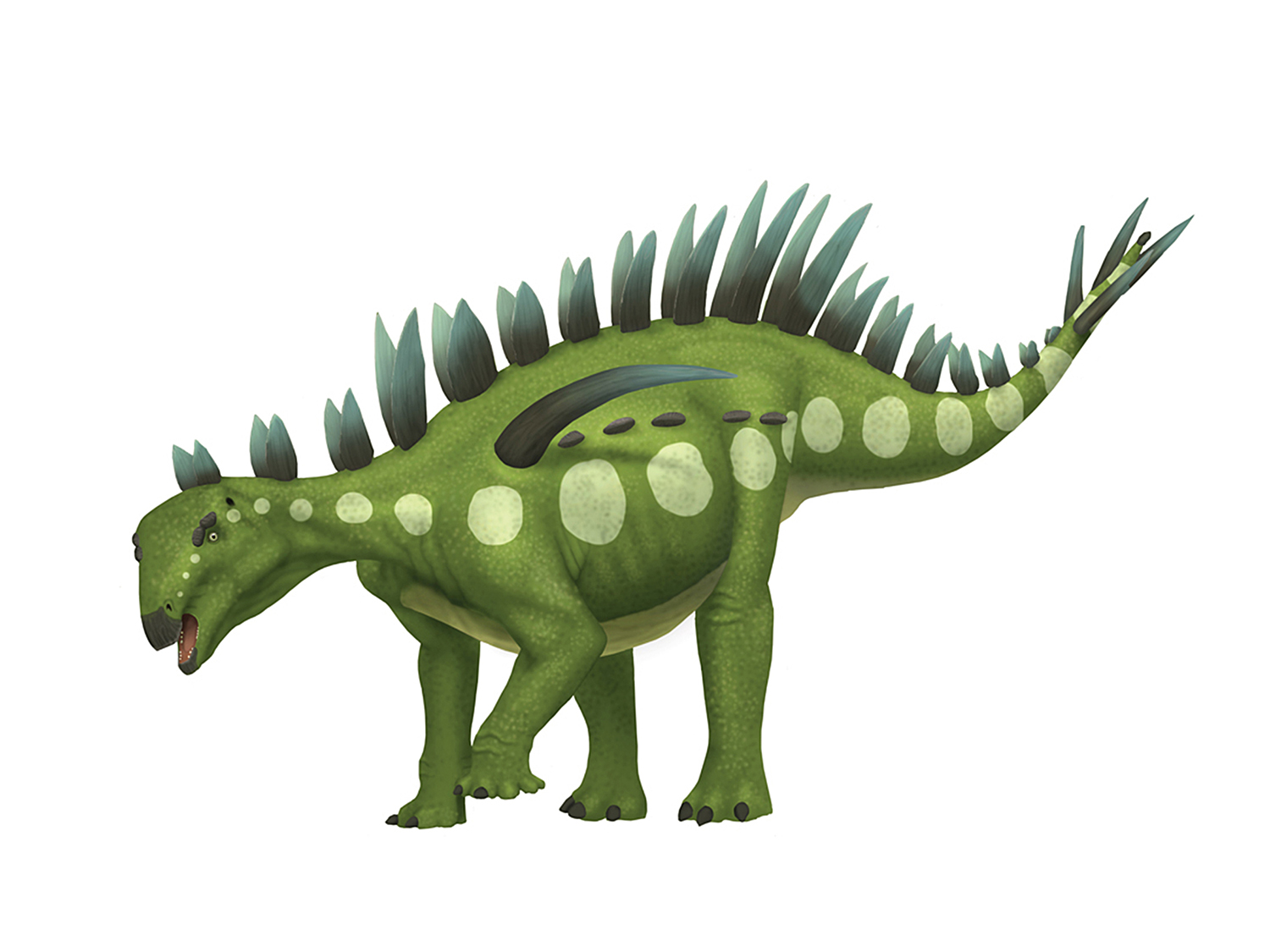

The tl;dr of the series was there is good reason to think no dinosaurs held their tails substantially above horizontal, and that past skeletals of hadrosaurs, sauropods, and/or stegosaurs that showed this (including my own) needed to be updated. Hence, no raised dino-butts. I had already updated my hadrosaurs to reflect this, and have steadily updated my non-diplodocoid sauropod skeletals. The impact of these changes, as I discussed in an SVP poster presentation back in 2012 is for the back to slope upwards, making the neck more vertical even without strong inflection in the vertebrate at the neck/back juncture.

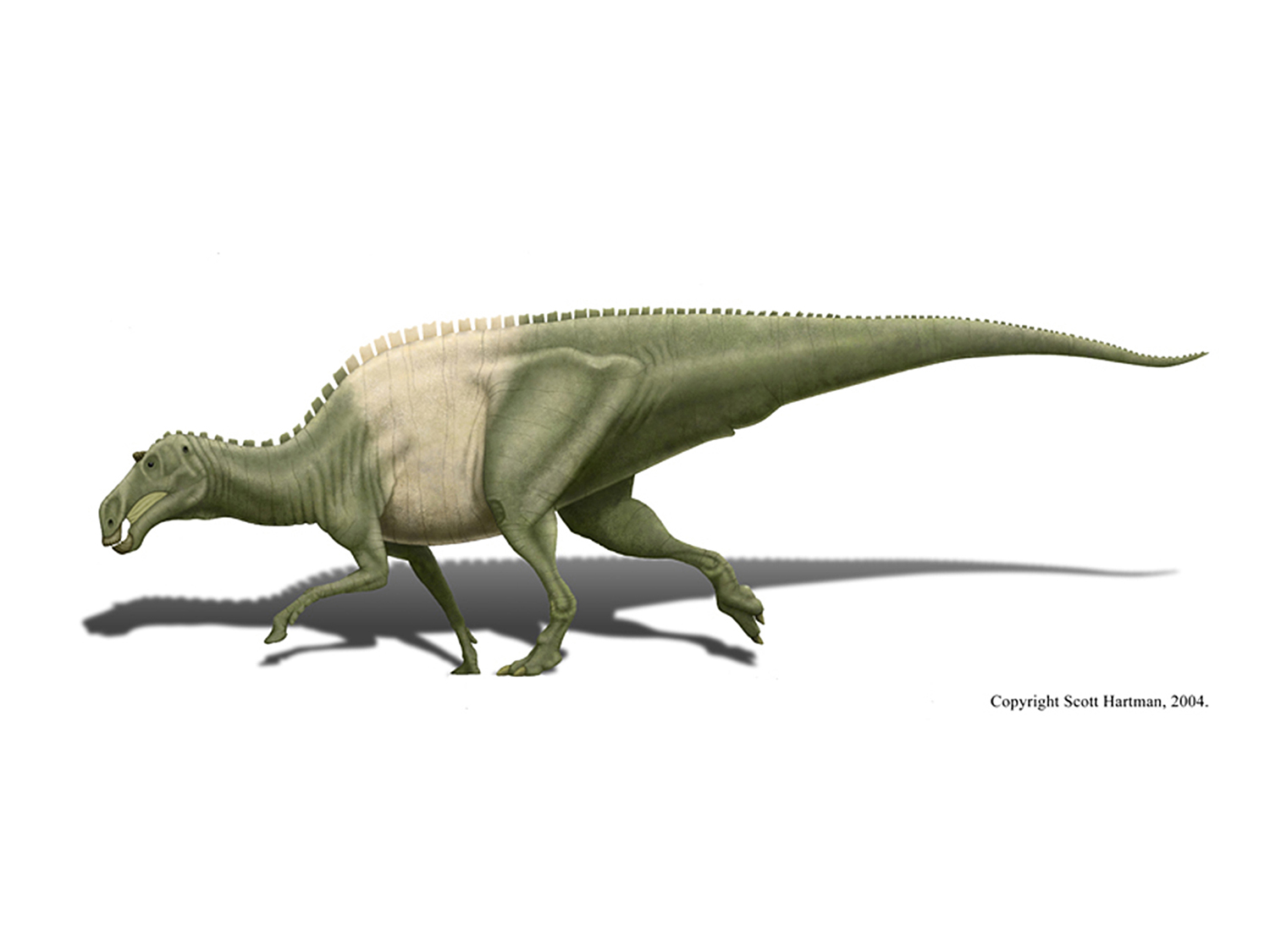

So…why this post now? And why so abbreviated? Because I no longer need to make the case for sauropods with horizontal tails and more upwardly sloping backs/necks, because a new paper by Daniel Vidal and coauthors makes the case directly from scanned bones, and does so far more effectively:

And the paper is open access, so hit up the link if you want to read it yourself! While the paper is mostly concerned with the primitive sauropod Spinophorosaurus (demonstrating in the process that it’s not just macronarians that were high browsers), there is a generous portion of supporting online information that demonstrates that the wedging of the hip vertebrae are found in many other sauropods groups, including diplodocids.

So this quick-hitter of a post serves two purposes. First, to alert you, dear reader, to some really cool new research that was published. Research that directly impacts paleoart, and moreover that does a lot of heavy-lifting (pun absolutely intended) for establishing sauropod posture. Second, it’s also here so I can warn you about the impact to my own skeletals. To one degree or another most of my non-diplodocid skeletals are congruent with Vidal, et al (2020), although a few of them need their backs to be raised a little bit more.

More problematic are my diplodocoid skeletals. I had previously reposed an Apatosaurus louisae skeletal along these lines in preparation for the tail series, but it looked so weird out of context I wasn’t going to post it until the blog post was ready. It’s now headlining this article, and if anything I don’t have the back angled upwards enough. But I will not have a chance to update any skeletals until mid-summer at the earliest, so if you are using one of my other diplodocoid skeletals, be forewarned that they will need varying degrees of adjustment to have more upright backs.

So get used to sauropods with more elevated back posture and (therefore) more upright necks. I’m looking at you, horizontal-necked titanosaur illustrations!

Fig. 1 from Vidal, et al (2020) showing the high-browsing adaptations of Spinophorosaurus.